|

Bio Reviews

Bette

and Joan:

The Divine Feud

Ferocious

Ambition: Joan Crawford's March to Stardom

Joan

Crawford: The Enduring Star

(2)

Joan

Crawford: The Essential Biography

(2) Joan

Crawford: Hollywood Martyr

Not

the Girl Next Door (2)

Starring

Joan Crawford

Bette

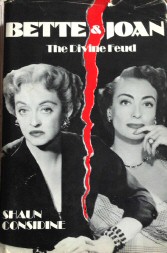

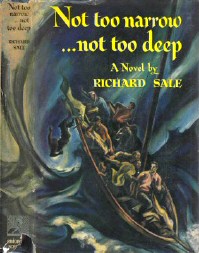

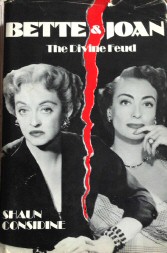

and Joan: The Divine Feud, by Shaun Considine Bette

and Joan: The Divine Feud, by Shaun Considine

Reviewed

by Louis, AKA LuLu (May 2006)

OK, this is a MUST READ for all Joan fans, especially those who

LOVE Bette Davis as well. The information you will get out of this book

is amazing; it's a running timeline of the lives of both Bette and Joan,

intertwining at precise moments in time. The day-by-day details from

the sets of Baby Jane and Hush...Hush... Sweet Charlotte make this an

even better read. The book is full of bitchy bitter quotes from both

Bette and Joan regarding themselves and each other. If you haven't read

this book yet.... What the HELL are you waiting for! Get your hands on

it now; I promise you won't be disappointed.

Ferocious

Ambition: Joan Crawford's March to Stardom Ferocious

Ambition: Joan Crawford's March to Stardom

Reviewed

by Stephanie Jones (October 2023)

- 1/2

of

5

- 1/2

of

5

First,

kudos to the author and the University Press of Mississippi for

this well-researched overview of Joan's life and career (the

first major Joan publication since 2009's Joan Crawford: The

Enduring Star by Peter Cowie). A professionally published, well-written

and annotated bio with good-quality photos is always a welcome addition

to the Joan literary canon (and a welcome relief from lower-end

Joan bios that invent conversations, give interminable plot summaries, and

rely too heavily on anonymous hearsay, as well as a relief from self-published

vanity affairs).

Here,

Joan's entire professional and personal story is told competently

and interestingly, the narrative obviously the result of a great

deal of research. The lengthy Notes section lists hundreds

of sources for the info that appears in the chapters: Joan- and

Hollywood-related autobios and bios, as well as articles from trade

and popular publications of Joan's period. There's not much new

or surprising info for a longtime Joan fan or scholar, but

for the general reader interested in Joan and wanting a concise

but detailed account of her life and times during the

Hollywood system and beyond, this book is definitely of interest,

both for its precise box-office stats and filming details,

as well as

the info from already published (but still

juicy) industry gossip and opinions perhaps not gathered in one

place before.

One

problem I did have with Ferocious is its schizophrenia

re its stated thesis (and title) of Joan's "ferocious

ambition" and determination being the reason for her decades-long

stardom (as touted by the book's promo material and intro) versus

some of the author's statements in the text.

In

favor of Joan's own ambition and determination: "Few of

us get to be our own Pygmalion, and for those who have managed to

do so, none have done it better than Crawford." And "Arnold's

magnificent photographs reveal the intelligence, strength---both

mental and physical---and most of all, the diligence that made her

a star."

But

then there's the exact opposite sentiment

from the author: "Crawford has a small group to thank for her

decades of motion picture success. Rapf, Mayer, Mankiewicz, Hurrell,

Adrian, and Gable, and to that list needs to be added Jerry Wald."

And "Without these three [Adrian, Hurrell, and Gable] Crawford

may never have become one of cinema's iconic figures." And,

rather confusingly: "[Crawford] was able to convince a series

of influential men that her determination and motivation might be

enough to propel her to success in show business." (I say "confusingly"

because I highly doubt that any of these men were thinking, "By

golly, little Billie has so much determination and motivation! Let's

hire her!" Rather, they probably found her sexy and thought

the public might do the same and thus make them some money. It was

up to "little Billie" to advance herself once these men

were done with her.)

Another

odd statement: "Had Crawford been wise

with her money, like Garbo and Shearer, she might have become

wealthy and could have decided to retire, or to make films for the

fun of it and not for the salary. But money slipped through Crawford's

fingers." First of all, the author, despite his book's promo

material, seems to completely miss the point of Crawford's

raison d'etre: She obviously loved to work, and she loved being

in the public eye. Her innate psychological need obviously had nothing

to do with the amount of money in her bank account. Especially given

this fact: At the time of her death in May 1977, her estate was

valued at $2 million. In today's dollars (https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm),

that's $10.5 million. Joan never HAD to work in her later years;

she WANTED to. (Re Garbo and Shearer: By the 1940s, they were no

longer relevant to the public; I'm sure this

was a primary factor in their "retirements." Oh, and Shearer's

husband, MGM big-wig Irving Thalberg, died in 1936; what a

coincidence that her career petered out upon his death!)

Another factual error in the book: The author says, re Grand Hotel:

"...it is doubtful [Crawford and Garbo] crossed paths while

the film was in production." Not according to Crawford herself.

See the transcript from Town

Hall in April 1973,

in which she breathlessly describes their meeting. (Biographer Bob

Thomas also confirms that Joan often spoke about her meeting with

Garbo, as well as their brief daily "good mornings.")

And then there's

this nonsensical bit re Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and his awareness,

or lack of, wife Joan's affair with Gable: "What seemed to bother

Fairbanks Jr. as much as the affair itself was that a favorite trysting

place [was a portable dressing room that Fairbanks had bought as

a wedding gift for Joan]. He was probably unaware of the new man

in his wife's life." --- Well, was Fairbanks aware or not aware

of the Gable affair?

Picture-wise,

the book is full of good-quality photos, usually placed right in

sync with what's going on in the text. The 16-pp centerpiece of

full-page glossy photos, though, has no rhyme or reason. No consecutive

years, no grouping of photographers. And one blatant error: One

publicity photo with Joan and Gable is described as being from "Possessed,

1932." First, the photo is from 1936's "Love on the Run."

And even if it were from "Possessed," that movie was released

in 1931. Globally, some notable omissions from the photos (probably

due to cost restrictions), though written about in the text: No

important photos from Eve Arnold, Karsh, or the final 1976 session

with Engstead.

Overall,

this a sound, serious book from a serious scholar and press.

A welcome and competent, though not particularly psychologically insightful

or 100% accurate, addition

to the Joan literary canon.

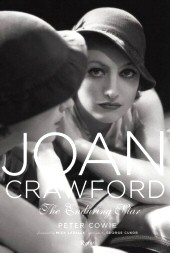

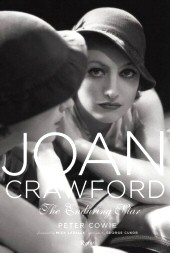

Joan

Crawford: The Enduring Star, by Peter Cowie Joan

Crawford: The Enduring Star, by Peter Cowie

Reviewed

by Stephanie Jones (February

2009)

of

5

of

5

Peter Cowie's

coffee-table book "Joan Crawford: The Enduring Star" is a lush photo-Valentine to Joan fans

old and new ... but especially the new.

I came of Joan-age in the mid-1980s, just in time to revel in Alexander

Walker's "The Ultimate Star," published in 1983, and the "Legends"

Kobal-collection photo book, which came out in '86. These two books, along with

"Conversations with Joan Crawford," published in 1980, helped solidify my Joan

fandom after I'd discovered her for the first time as an actress---in a VHS

rental, "Grand Hotel," watched from a hard chair on a tiny screen in a

university library.

I suspect that the photographs of "The Enduring Star" will act for a new

generation of those teetering on the brink of Joan-fandom as a similar catalyst:

enough to send 'em over the edge into either full-blown admiration (if they're

the purely visual sort), or into a quest to learn more about her films before

they make up their minds. Whichever the case, the book has done its job. As film

critic Mick LaSalle says in his introduction: "Look at that face--modern, arch,

knowing, passionate, ready to eat the world. That's still something new, that's

today looking right at you." Indeed. You can't look at that face and not

react to it.

Admittedly,

when it was first announced in June 2008 that LaSalle

would be

writing the introduction to a book about Joan Crawford, I was immediately wary.

He was, after all, a high-profile Norma Shearer-booster, and one who often

dissed Joan in the process of boosting Norma (or just dissed Joan for the hell

of it). His 2000 book "Complicated Women," for instance, includes such semi-bon

mots as: "Crawford [in her early-1930s performances] looked like an act trying

to impersonate a human being. Emotional problems certainly contributed to this,

her image didn't help." Later

in the book, he cattily says Crawford's onscreen energy is that of "a woman

dancing fast to keep the whorehouse customers happy."

LaSalle now seems to have

amended his cat-calls in time to contribute to his colleague Peter Cowie's book. He gives

Joan more than a fair shake in his appreciative intro, as when he writes: "When

you see her, you'll feel, maybe for the thousandth time, maybe for the precious

first time, what she meant to the fans who originally discovered her. That

should be our goal, to see Joan Crawford fresh, for the work she did. She and we

deserve nothing less."

The book's primary strength lies in its thoughtfully chosen,

gorgeous photographs, which do indeed enable even long-time fans to "see

Crawford fresh." As a long-time fan myself, I enjoyed rediscovering and

appreciating Joan's face anew with each turn of the page.

The selection of publicity shots, films stills, and a

smattering of candids tilt heavily toward her 1930s images, with a focus on

Hurrell's work. That her post-1940 period isn't better represented is a bit

disappointing (post-1940 pictures comprise about a fifth of the book's total);

Joan had some stunning sessions during the '40s, for instance, with

photographers like Bert Six and Whitey Schaefer, and it's a shame that their

work, and more of Laszlo Willinger's late '30s sessions, didn't receive more

attention. The dearth of Ruth Harriet Louise's seminal 1920s shots is also

regrettable.

Another quibble: The book-jacket claims that more than 100 of the photos here

have not been seen in the past 25 years. The author seems to have forgotten the

miracle of the Internet! As the webmaster of a Joan website with a photo gallery

consisting of literally 1000s of photos, I've spent the past 5 years compiling

Joan photos from various sources for the gallery. I counted the photos in this

book that I haven't yet seen: 53 of the 213. While the claim of "more than 100"

might be off, for a regular Joan-photo-searcher like me to have not seen a

fourth of the photos is, nonetheless, a more-than-respectable accomplishment.

And for the average Joan fan, or especially the Joan beginner or the merely

curious, the selection here is an absolute treasure trove, destined to create

new admirers or to turn what might have begun as only a passing interest into a

full-fledged obsession. As director George Cukor writes, from his 1977 eulogy in

this book's Afterword: "She had...above all her face, that extraordinary

sculptural construction of lines and planes, finely chiseled like the mask of

some classical divinity from fifth-century Greece. It caught the light superbly.

You could photograph her from any angle, and the face moved beautifully...The

nearer the camera, the more tender and yielding she became -- her eyes

glistened, her lips parted in ecstatic acceptance. The camera saw, I suspect, a

side of her that no flesh-and-blood lover ever saw." The photos in "The Enduring

Star" manifest the face of Cukor's words religiously.

Despite the

glory of the photographs, the text of the book is, however,

primarily filler. Almost all of the

information comes from other biographies, and Cowie heavily pads the text with

lengthy plot details of the movies. In addition, the author gets a few facts

wrong, including the howler that Marie Dressler was considered for the part of

Flaemmchen in "Grand Hotel," and that "Flamingo Road" takes place in either

Missouri or Mississippi (it's set in Florida). And a couple of photos from the

1930s show up in the 1940s section. Cowie also descends to the borderline-creepy

on a couple of occasions, a la biographer David Bret, as when he waxes

lascivious about Joan's sexuality: "When [Johnny Guitar] displays his

sharpshooting skills, Vienna hisses, 'Give me that gun!' It's a moment of sheer

emasculation, and one senses that the whip and the paddle are but a heartbeat

away..." Then later there's: "[I]n private life she still craved a man whom she

could respect, even if she would invariably wear the trousers in domestic (and

perhaps sexual) terms."

This type of sniggering prose is not only annoying, but also incorrect: While

conventional wisdom has it that Joan was a real ball-buster, in reality, her

primary relationships were with men more accomplished than she, and as strong,

if not stronger. Husbands Doug Fairbanks Jr. and Franchot Tone were both willful

and cultured, and Joan played the willing pupil to each. Pepsi president Al

Steele was certainly no shrinking violet himself; nor were long-time lovers

Clark Gable and Greg Bautzer, both known for their dominant personalities. For

real psychological insight into the woman, one does better to turn to Alexander

Walker's "The Ultimate Star." Here's Walker's more insightful analysis of her

androgynous quality, as he discusses Sadie Thompson in "Rain": "[Director Lewis

Milestone] reveals the male will that inhabits Sadie's assertively female body.

This is precisely the conjunction that fascinates many of Crawford's admirers

today, even those who do not find her sexually attractive. She is a woman with

power over men -- and part of that power is the disconcerting discovery a male

makes that the power is of the same gender as himself. It proved too unexpected

a change, too raw a demonstration, for Crawford's fans to accept in 1932."

Despite Cowie's occasionally simplistic overview of Joan and her career, and

the infrequent error, his text is, however, for the most part competent and

well-researched. Mid-level and hard-core Joan fans won't learn anything new from

the text, but for beginning fans, it is a helpful, clear, and detailed

introduction.

Another strength of the Cowie book lies in its professionalism. The

publisher, Rizzoli, is known for quality coffee-table books, and this Joan-book

lies in the company tradition, a welcome relief from the recent spate of amateur

contributions to the "Joan canon." (The recent David Bret bio was a rehash of

former biographies combined with filler plot details and goofy asides; the

Charlotte Chandler book was, despite including author interviews with Joan,

rather sloppily patched together, also padded with unnecessary plot recounting;

the "Letters" book by Michelle Vogel was amateurishly organized, filled with

factual and grammatical errors, and accompanied by illegally-reproduced photos

on poor-quality paper.) "The Enduring Star," on the other hand, is thankfully

all-pro, with its glossy pages and its adherence to publishing conventions: It's

been properly edited and copy-edited, with actual photo credits, source notes,

and a complete Filmography that clears up one mystery about some of Joan's early

films. The inclusion of the complete text of director George Cukor's insightful

posthumous 1977 eulogy as an Afterword, which I'd previously only read snippets

of, is also a welcome addition to in-print Joan information.

"The

Enduring Star" is a high-quality contribution to Joan's legacy.

I

recommend it for staunch fans, neophytes, and Classic Hollywood photography

connoisseurs alike. A glamorous tribute in recognition of a face, and of

a woman and actress, that both embodies and transcends

her era.

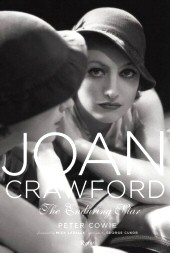

Joan

Crawford: The Enduring Star, by Peter Cowie Joan

Crawford: The Enduring Star, by Peter Cowie

Reviewed

by Mike O'Hanlon (December

2014)

of

5

of

5

Peter Cowie’s Joan Crawford: The Enduring Star serves a main purpose for those individuals who just want to look at a young, beautifully photographed, glamorous Joan. The book does have a larger purpose Cowie may not have envisioned during his work on the project: a realization of how (and sadly why) these big, expensive books have seen an unfortunate demise…the Internet! While the book does have a huge amount of images which I was not familiar with, many I have seen lingering around on different websites for years. Some of the photos (one in particular of Joan Crawford and Franchot Tone in Dancing Lady) I can remember first seeing in The Films of Joan Crawford, which was published in 1968!

There are those of us who do want physical copies of these photos in books such as Enduring Star, maybe for when we want to get away from technology and sink into some other source of entertainment. And the text itself is well

written and informative for new fans of Joan. (For those of us who’ve known Joan for at least 10 years or longer, eh… nothing new here. But it’s well written, so at least it’s not a bad rehash of previously known information.) So the book is a good collector’s item to own.

A foreword by Mick LaSalle and an afterword by George Cukor (obviously pulled from his own words about Joan written many, many years ago when she passed away in 1977) complement the book. I mean, the afterword by Cukor anyone can pull up on a Joan site, but the foreword by LaSalle was interesting. I knew people in the Joan community were a bit skeptical because not since Bosley Crowther’s initial reviews of her films in the New York Times had a critic tore Joan to shreds. LaSalle’s 2000 book Complicated Women: Sex and Power in Pre-Code Hollywood really seemed out to echo Crowther’s own opinions of Joan and her acting abilities. Enduring Star focuses on Joan’s major years at MGM and sort-of touches on her Warners years. After that, her freelance career and unfortunate shameful demotion to cheap, tawdry horror flicks are summed up in a few pages. I didn’t understand why at first. Then I remembered all the different people in my life who have seen photos of a young Joan Crawford through me and cannot believe it’s her. Between that and Cowie’s book, it does awaken me to the realization that the general public still does view Joan Crawford as some horribly made

up drag-look-alike who spent the bulk of her time in bad movies and bullying children off the screen.

And perhaps that’s why Cowie set out to remind the general public of who the real Joan Crawford really was… either way it just seems a bit uncertain.

Joan

Crawford: The Essential Biography, by Lawrence J. Quirk and William

Schoell Joan

Crawford: The Essential Biography, by Lawrence J. Quirk and William

Schoell

(2002,

University Press of Kentucky)

Reviewed

by Mike O'Hanlon

(February 2011)

of 5

of 5

This “essential” biography really isn’t all that essential to a Joan Crawford

fan, particularly one who knows a lot about Crawford and has seen as

many of her films as I have. I will say, however, that this is a very

good introductory biography to fans who are just getting their interest

sparked by this remarkable woman whose extraordinary career lasted

forty-five years.

My biggest problem with the book (and the title

gives this away) is that it tries to be smarter than it really is. Quirk and

Schoell really write about some of this material as if it were never

before discussed in previous books about Joan Crawford. And in some

cases, there is mentioning of some material that I had not been keen on

before I read this one, but most of the information was

sexually-oriented. Quirk (and I believe Quirk largely wrote this one;

I’ll explain later) goes into detail about how his uncle, editor of

Photoplay magazine James Quirk, was one of many men who secured

Crawford’s position as a top Hollywood star in return for sexual favors.

This book makes no attempt to disguise the fact that Joan Crawford got

to the top with a mattress strapped to her back, even quoting Joan as

having said the father of silent film child star Jackie Coogan was a “dirty pig!”

A good writer could have worked this material into a

more intelligent analysis. But in this case, it comes off as gossipy

and rather immature and childish.

Another big

problem of mine with this one is its constant, and rather lackluster,

attempts to dismiss the allegations made against Joan Crawford by Christina Crawford in Mommie Dearest. Really, as a Joan Crawford fan, I’m so sick of this. Mommie Dearest is bullshit, I get it. Can we discuss something else about Joan now?

I mentioned before that I believe that Quirk wrote

the majority of this book, and I’ll tell you why. First of all, he makes

constant reference to his uncle, even supplying a glossy photo of

him… Listen, I bought this book to read about Joan Crawford, not to look

at your fat, sweaty pig of an uncle who apparently forced girls to sleep

with him so they can become famous.

Second of all, I have read Lawrence

Quirk's books about Joan Crawford’s films and his biography of Norma Shearer. I’ll tell you this right now:

This biography of Joan Crawford was an almost exact replica of his Norma Shearer biography. (Christ, I think the chapters on The Women

are the exact same!) Instead of overanalyzing Norma’s movies, giving

his critical critiques, he just rewrote the plots. He does that here

with Joan’s films. He made constant reference to James Quirk in Norma’s

biography, the difference being Norma’s relationship with James Quirk

was not sexual. But he did repeat about how James Quirk helped Norma

become a major star by giving her good loan-outs before she hit it big

at MGM with He Who Gets Slapped

(1924), and two other big ones: Lady of the Night, and The Tower of

Lies (both 1925), which, according to numerous writers about Shearer,

secured her place as a star in Hollywood.

How could a man who worked for Photoplay magazine

have such control over the careers of at-the-time nobodies whom none of

the big executives at MGM cared about? How could a man in his position

even manage to meet them? I would imagine someone in that high of an

editorial position at the biggest movie magazine in the country in 1925

would be chasing after the Gloria Swansons, Mary Pickfords, and Corrine Griffiths. Not the unknown starlets who come and go so quickly.

Another fact that caught my attention in his book

about Shearer was his way of describing certain movies of Norma’s that

have been lost for decades. Movies he could not have possibly seen,

which leads me to believe some of the book was largely fabricated, as is

this one. It’s a frustrating book. Good for first-time

readers, but bad for knowing fans. And for those who think this is a

good one…hey, make sure to say a prayer every night to James Quirk.

Without him, we wouldn’t have Joan Crawford or Norma Shearer to talk

about all these years later.

Oh, and be prepared for a lot of beautiful pictures

of Joan throughout the text. They are pretty, superficial pictures, yes.

But he should have organized them with the text. Why use a photo of

Joan from 1931 to write about her life in 1945? Or a photo from 1940 to

discuss her career in the 1960s?

Joan

Crawford: The Essential Biography, by Lawrence J. Quirk and William

Schoell Joan

Crawford: The Essential Biography, by Lawrence J. Quirk and William

Schoell

(2002,

University Press of Kentucky)

Reviewed

by Matthew

Kennedy in Bright

Lights Film Journal

(2002)

Joan Crawford was not Mommie Dearest. In the expert new biographyJoan Crawford, co-authors Lawrence J. Quirk and William Schoell dismiss Christina’s efforts to forever encase Crawford in

grotesque motherhood. To Quirk’s and Schoell’s credit, they avoid the

opposite tone and steer clear of gushing fanzine hyperbole. The woman

who emerges from these pages was tough, demanding, self-obsessed, horny,

generous, and loyal.

The subtitle of this book, the essential biography, actually does the

work a disservice. The essential biography would be longer than these

294 pages, and include exhaustive library, archive, and first-person

sources. This book is more a personal reflection, as Quirk knew Crawford

for many years and heard firsthand her innumerable tales of life in

Hollywood. Joan Crawford is therefore all about her career, but it

doesn’t probe as much as it offers a chronology of her life in movies.

To further boost Joan Crawford‘s compulsive readability, the

authors do a fine job of discrediting Christina with ample opposing

testimony to Crawford’s character. And anyone looking for potshots at Esther Williams, Marilyn Monroe, and Faye Dunaway won’t be disappointed.

We are first taken to Crawford’s scruffy childhood in Texas and the

Midwest, but soon the former Lucille LeSueur is bewitching the early

moguls of Hollywood as the flapping starlet of such light efforts as Pretty Ladies, The Boob, Tramp Tramp Tramp, and The Taxi Dancer. One is reminded that she later made her share of decent movies — Possessed (1931 and 1947), Grand Hotel, Rain, The Women, A Woman’s Face, Mildred Pierce, Humoresque, Flamingo Road, Sudden Fear, and the delectably off-kilter western Johnny Guitar.

I’ve always had a soft spot for Crawford in the 1950s, when she was

vainly hanging on to the glamour girl image just as her key light got

brighter and the camera lens got softer. It’s hard to watchThe Damned Don’t Cry, Female on the Beach, and Autumn Leaves and

not see a hybrid of actress-woman clinging to her sexually ripe

hardscrabble survivor persona. It makes for compelling screen acting.

The strength of this book, with its attention on her epic career, is also its weakness.Joan Crawford at

times can’t helping lapsing into predictable rhythms. (Fill in the

blank) is given a plot summary, made, released, and ranked on an

unofficial scale from Mildred Pierce to Trog. Crawford

(loved/hated) that movie and (loved/hated) her co-stars. The next movie

is treated similarly, and the one after that. This gives the reader an

appreciation for the assembly line of studio era Hollywood, but it dims

any chance of deeper insights on Crawford’s life and work. The authors

don’t hesitate to take on her whispered bisexuality, or mention a

little-known affair she had with Jimmy Stewart, but these nuggets appear

only in passing. Marriages are made and broken, children are famously

adopted and prove less than angelic, MGM lets Crawford go, she gets her

revenge at Warner Bros., marries Pepsi nabob Al Steele, and does a

sadomasochistic tango with Bette Davis in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? It’s all here, but one longs for more depth with Crawford the woman. Where Mommie Dearest was all domestic drama and little appreciation for Crawford the star-actress, Joan Crawford is quite the opposite.

Perhaps that is the unwritten message of Joan Crawford — that the

woman and the star were one. What a startling contrast Crawford was to Grand Hotel co-star

Greta Garbo, who spent half a century running from fame, wandering the

streets of New York like a confused and frightened stray cat. Crawford

couldn’t have been made of more different temperament. She carried

herself as though stardom was her birthright. She reveled in it, sought

it and expected it, as though she forever imagined a sparkling tiara

affixed to her well-coiffed scalp.

Crawford has been dead 25 years, yet her ghost defies obscurity just

as the woman did in life. Of course her career went south and the

pictures got small. Toward the end she was reduced to changing costumes

in a car. Still she carried herself with shoulders back and head held

high. Now that she’s gone, we forgive her those last pitiable years, and

hope she forgave the powers-that-be who wasted her talents. Time has

proven her durability. Don’t we love the élan, the chutzpah, and the

sheer force of character that makes for such rare beings as Joan

Crawford?

Quirk and Schoell are two film gentlemen-scholars who have at last

repaired the maligned Crawford legacy. She doesn’t deserve the easy

jokes begat by Christina’s ulterior attacks. At the end of the movie Mommie Dearest,

the disinherited Christina (played by the odd Diana Scarwid) alludes

that she’ll have the final say on her Gorgon of a mother. Quirk and

Schoell made sure that didn’t happen, and they are to be saluted for

their effort at fair appraisal. Enough time has passed to prove that

Joan Crawford doesn’t deserve wire hangers. She was and is an enduring

star, one of the great ones.

Joan

Crawford: Hollywood Martyr, by David Bret Joan

Crawford: Hollywood Martyr, by David Bret

Reviewed

by Stephanie Jones (April 2006)

of 5

of 5

There's

not much new or interesting in Martyr. It consists for the

most part of rehashed quotes from other

Joan sources and is heavily padded with the author's own (interminable)

retelling of film plots. (Even the cover is a rehash---with the

photo used already for Walker's Ultimate Star.) And no, there's no proof herein that Joan worked as a prostitute or

appeared in a porno (much less did so at the urging of her

mother!), as claimed on the dust jacket; and, after reading, I'm still wondering which 3 of Joan's

husbands were supposed to have been gay (as the dust jacket also

proclaims)! Bret mentions Franchot

being serviced by a man or two---OK, chalk one up to "bi" but

other than that, nothing. (Also, if I have to read of one more actor

described as "ethereal-looking" by Bret, I'll shriek.

I stopped counting at "4," but the list ludicrously went

on...)

On

the plus-side, the book does have several photos that I'd never

seen before. But unless you, like me, are collecting every

single Joan book just to have them, you really don't

need this one. I'd rank it down there at the bottom of Joan bios,

along with "Crawford's Men."

Not

the Girl Next Door, by Charlotte Chandler Not

the Girl Next Door, by Charlotte Chandler

Reviewed by John Epperson in the

Washington Post (Feb. 24, 2008)

Like other entertainment icons of the

20th century, such as Elvis Presley, Marilyn

Monroe and Judy Garland, Joan

Crawford represents the best and the worst of the American

dream. Crawford's was a grand success story from poverty in the Midwest to glory

in Hollywood and New

York. Presley, Monroe and Garland garnered cult fame, and

Crawford acquired a similar kind of worshipful sect that continues to grow

thanks to DVDs, Turner Classic Movies (which will broadcast 17 Crawford

films in March, the month of her centenary), and Web sites such

as

joancrawfordbest.com, an online encyclopedia devoted to

Crawfordism and regularly updated with photos and information about the Goddess

Joan. But also like the other three, Crawford had private demons with which to

grapple.

The press never

revealed Crawford's dark side of drinking and sexual peccadillos while she was

alive. It was her eldest daughter, Christina Crawford, who characterized her

(after Joan's death) as an abusive shrew in the bestselling

Mommie Dearest, which went on to become a notorious

film starring Faye Dunaway. Unfortunately, nowadays most people

think of Crawford as the monster of that 1981 film.

Charlotte

Chandler's new book, Not the Girl Next Door, tries to refute the image of

Crawford as a domestic fiend by telling the star's side of the story as gleaned

from extended interviews with her in the mid-1970s (Crawford died in 1977).

Chandler cites several of Crawford's friends and acquaintances as being upset

with Mommie Dearest, including Myrna Loy, who called

Christina "vicious, ungrateful, and jealous." The controversy continues among

Crawfordites, who will love this new book because it is, at last, pro-Joan.

Regrettably,

since the book is mostly quotations (from sources such as director George Cukor,

Loy, husband Douglas Fairbanks Jr., daughter Cathy, nemesis Bette Davis, etc.),

it has a sketchy, anecdotal quality that makes for jumpy reading. The reader

must fill in the blanks of the complex, contradictory actress's life. If the

reader already knows a great deal about St. Joan, sealing up the cracks poses no

problem. However, a novice Crawfordite might be stymied by the jump-cuts.

Chandler has turned out several books of this kind, on subjects including Billy

Wilder, Alfred Hitchcock, Bette Davis and Ingrid Bergman,

calling them "personal biographies," perhaps in an attempt to justify stringing

together lengthy quotations from the subject and his or her contacts. But no

matter how it's labeled, her approach doesn't make for smooth narrative.

Other portraits

of Crawford have appeared over the years, one of the most entertaining being

Carl Johnes's Crawford: The Last Years, a slim 1979 paperback.

Johnes was an assistant story editor at Columbia

Pictures' New York office when he met the star, who became his

doting friend. Johnes made a particularly valuable contribution to understanding

Crawford by disclosing her rather late-in-life identity search. Here was a woman

born Lucille LeSueur (her real name, in spite of its theatricality) who then

became known as Billie Cassin (she was a tomboy when her mother married a second

time, to Mr. Cassin). Later, in Hollywood, she became, briefly, Joan Arden, a

name picked for her in a magazine contest, and finally Joan Crawford,

manufactured celebrity from the dream world of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, purveyor of

glossy illusions. Who wouldn't have an identity crisis after all that? I've

attempted to live in Crawford's head a bit myself when performing my show "The

Passion of the Crawford," and it's a dangerous space to occupy, with its

constant vacillation from grand lady to goodtime gal to businesswoman to needy,

insecure, controlling star.

The most amusing

part of Chandler's book is the account by director Vincent Sherman, who made

three films with Crawford. His bizarre tales include attending, with Crawford, a

private screening of her film "Humoresque." As the movie unspooled, Crawford

became increasingly, erotically mesmerized by her own celluloid self and offered

to make love to him right on the spot, oblivious of the projectionist in the

back of the screening room. Sherman was able to get her to her dressing room,

where their affair began.

But Chandler pads

her book with awkwardly inserted synopses of Crawford's films, and some of her

"facts" are incorrect. For instance, in her summation of the lurid 1965 thriller

"I Saw What You Did," Chandler says that Crawford's character, Amy Nelson,

protects the three threatened female youngsters in the movie. Actually, Amy

encounters only one of the girls, to whom she is physically and verbally

abusive, repeatedly bellowing, "Get outta here!" Hardly protective.

The book also

suffers from careless repetition. On page 239, Chandler tells the reader that

after her last husband died, Crawford had to move to a smaller apartment in New

York because he had left so many debts. Two pages later, the author delivers the

same information.

This is only one

example of avoidable repetition. Perhaps it's very Joan Crawford of me to expect

a book to be tidier and more disciplined (imagine the neatness hell that

Crawford put her editors and co-authors through when she wrote her own books,

A Portrait of Joan and My Way of

Life), but I will give in to my (possibly neurotic) desire

for perfection and report that a fully satisfying Crawford biography has yet to

be written. Still, despite its drawbacks, even the most regimented Crawfordite

can enjoy Chandler's new book.

Not

the Girl Next Door, by Charlotte Chandler Not

the Girl Next Door, by Charlotte Chandler

Reviewed by Thomas

Mallon in The Atlantic (April 2008)

EDITOR

NOTE: Below is an excerpt; to read the review in its entirety,

visit The

Atlantic

website (subscribers only, although 1 or 2 free articles are

allowed per month), or click here

to read the full transcript on this BOE site.

‘I Am Joan Crawford’Through

sheer force of will, Hollywood’s most infamous single mother

constructed a persona seductive, repellent, and almost impossible not to

watch. Like many of her awful but absorbing movies, this new biography of Joan

Crawford (1908?–1977) begins at the end of the story, before flashing

back to Reveal All. Not the Girl Next Door opens with an

interview that Charlotte Chandler, the author, once conducted in

Crawford’s New York apartment (“I sat on the sofa after she removed its

plastic cover”) with the retired and aging star. The actress speaks in

the noble Photoplay tones (“I wouldn’t change anything for fear

of changing it all”) that were always a large part of Crawford’s stiff

public image, until it was toppled like a dictator’s statue by her

adopted daughter’s poisonous memoir, Mommie Dearest. ...

...Crawford’s was a life less lived than produced, a joint venture

undertaken by herself and MGM, and though it’s been much better

recounted in previous biographies (one by Bob Thomas, another by

Lawrence J. Quirk and William Schoell), the chance to gawk at its sad

closing and then work backward, peeling off the layers of metallic

maquillage, remains a sordid thrill....

Crawford didn’t live to see the publication—and, worse, the filming— of Mommie Dearest,

but she has had numerous defenders in the years since, and her new

biographer is firmly in the pro-Joan, anti-Christina camp. Chandler

offers testimony from friends and family that the daughter had always

been impossible, and her brother even worse. Myrna Loy, speaking of

Christina, once told Lawrence J. Quirk: “Believe me, there were many

times I wanted to smack her myself.” ...

Chandler’s idea of retributive justice is to overaccentuate anything

positive about her subject. She creates a fanzine Saint Joan (“She felt

it was selfish to have household help during World War II, when there

was a labor shortage”), but that’s the least of this book’s flaws.

Quotations are flung upon the page with no hint of a source or date, and

long, inane plot summaries of Crawford’s films pad the text more

outrageously than Adrian ever filled out the star’s shoulders. Almost

everything else is underdeveloped, devoid of context, and badly located,

as if the biographer were some incompetent prop mistress, misplacing

all the glamorous clutter from the life of her subject, who, it’s fair

to say, would have hated this book for its sloppiness....

Starring

Joan Crawford: The Films, the Fantasy, and the Modern Relevance

of a Silver Screen Icon, by Samuel Garza Bernstein Starring

Joan Crawford: The Films, the Fantasy, and the Modern Relevance

of a Silver Screen Icon, by Samuel Garza Bernstein

Reviewed

by Stephanie Jones (June

2024)

- 1/2

of

5

- 1/2

of

5

For me,

the apex of Joan Crawford bios is Walker's The

Ultimate Star (1983). Starring

Joan Crawford is very like Ultimate in some important

ways, primarily its author's intelligently conversational and

alert writing style that adeptly intersects biographical,

film, sociological, AND psychological information into an enjoyable

and comprehensive narrative of JC's Life and Times. You don't just

get a stale retelling of facts and films, but rather a sense---via

the author's insightful and skilled narrative that includes

quotes from Joan herself as well as contemporary interviews and

film reviews---of who she was; what she was feeling; and what

she, and her film roles, represented to the public during

each phase of her life and career.

Written

in the present tense, Starring is also very reminiscent of

the style of Norman Mailer's famous Marilyn (1973). While

Mailer has been, at least since the '90s, automatically

(and ignorantly) looked down upon by leftist academics as a

macho caveman, it seems obvious that the non-caveman, loud-and-proud LGBTQ+ Garza

Bernstein has read Marilyn and learned from it, both

stylistically and in terms of male empathy for a female figure.

Here's Garza Bernstein on Joan:

In

her wildly popular Cinderella stories at MGM there was very little

bitterness. She was young, beautiful, resilient, and able to adapt

herself to the circumstances she found herself in---however unfair

they might seem. From Mildred Pierce through the rest of

her Warner Bros. years, she is more often than not an adult Cinderella

who has been knocked around by life and is no longer willing to

adapt to anything for anybody. Things are going to be her way. If

she is treated unfairly, there will be hell to pay.

And

here's Mailer on Marilyn:

The

amount of animal rage in her by these years of her artistic prominence

is almost impossible to control by human or chemical means. Yet

she has to surmount such tension in order to present herself to

the world as that figure of immaculate tenderness, utter bewilderment,

and goofy dipsomaniacial sweetness which is Sugar Kane in Some

LIke It Hot.... She will take an improbable farce and somehow

offer some indefinable sense of promise to every absurd logic in

the dumb scheme of things....

As

interestingly and well-written as I think Garza Bernstein's primary

text is, there's also an awful lot of padding/filler in the book.

Of the 223 "official" pages, there are only 189 pages

of actual text (not including pp. 191 thru 223 of back matter).

And of the 189 pages of actual text, a whopping 63 pages (fully

one-third) are taken up solely with film synopses/credits, and another

28 pages with transcripts of 5 actual magazine articles (no

authorial interpretation, just straight texts), plus pages at the

end of each of the five chapters with ridiculous made-up

scenarios re "if Joan were alive today and appearing in"----as

in "Barbie," "Doctor Strange," "The Eyes

of Tammy Faye," et al. Not clever at all, and a real detraction

from the rest of the book. Here's an example of some highly cringe-worthy

"fantasy" text at the end of the first chapter (let me

reiterate: All of the chapters actually have serious, thoughtful,

researched text---until we get to this type of thing):

She

smashes it at the box office playing the title role in Barbie

with a "totally ironic twist that's so not ironic"

and then surprises everyone when she gets engaged to Doug Fairbanks

Jr. ("JR") by posting it old-school on Facebook. "He

popped it and I said YESIII (OMG meeting his PARENTS!) #JC+JR=jodo4ever."

These

dumbed-down "Fantasy" bits are a severe mistake

by both author and book publisher Applause (are there any editors

left at any publishing houses?). Aside from the above end-of-chapter

mistakes come multiple already-passe-in-2024 pop-culture references

by the author, like this one (which has nothing to do with Joan

Crawford):

After

triggering a public backlash about her own sensistivity to people

with food sensitivities, [Demi] Lovato posts, "It wasn't clear

to me that it was for specific health needs, and so I didn't know

that."

Also

forcibly, nonsensically, un-cleverly inserted in the text

(at least in early chapters; the author eventually calms down):

Random podcasters, Love Island, Taylor Swift, Britney Spears,

Miley Cyrus, Ariana Grande, Selena Gomez, Lady GaGa, Emma Stone,

Kylie Jenner. All of whom have absolutely NOTHING to do with Joan

Crawford----who was, by all accounts, despite the media hype that

surrounded her and her own self-promotion, a basically sincere,

hard-working, very talented person who actually captured the

zeitgeist of a nation, and world, for over 40 years.

Photo-wise:

Starring has 124 pages of photos, with 32 color glossy photos.

As I've complained re previous books, there seems to be an only

rudimentary sense of organization. (Again: Where are the editors

at publishing companies today?) In the case of Starring,

the five photo sections are arranged chronologically about 80% of

the time, with a lot of random things stuck in. (For instance: At

the end of the "Mother and Martyr" Section 3 of text,

the photos start with a 1930 Photoplay cover----this time

period was already covered over 50 pages ago, with its own photo

section.) It's also incredibly annoying to see faded black-and-white

stills from films that have been ostensibly "restored"

by the author (as he states in the Intro); the "restorations"

look blatantly fake. The clumsy photo modifications are clearly

a work-around to avoid actually paying for photos. (Again, what

ever happened to actual publishing companies that once included

real photos that they paid for?)

In

short: Samuel Garza Bernstein is a very good writer, and his book

about Joan definitely has merit----if you delete all of the "Barbie

Fantasy" stuff, and don't expect too much from the photos.

Misc.

Reviews

Conversations

with Joan Crawford The

Other Side of My Life

Conversations

with Joan Crawford Conversations

with Joan Crawford

Reviewed by Richard Brody in the

New York Times (September 13, 2011)

Joan Crawford: The Voice

A few weeks ago, while discussing

“Johnny Guitar” here, I cited an acerbic remark of Joan Crawford’s about the film which I

found in Patrick McGilligan’s new biography of Nicholas Ray—and which he, in

turn, got from another book, “Conversations with Joan Crawford,” by Roy Newquist,

from 1980. The remark was sufficiently unguarded, and the readers’ reviews on

Amazon sufficiently enticing, that I ordered at once a copy of the

long-out-of-print book—and am I glad I did.

In his preface, Newquist explains that he met Crawford twenty-one times

between 1962 and her death, in 1977 (“after our third meeting she allowed me to

take copious notes”), and expresses his confidence that, in these interviews,

“the reader will find a Crawford revealed more candidly than in any other

printed interview or biography.”

I’m

not a connoisseur of the Crawford literature, but the voice that emerges in

Newquist’s book is indeed extraordinarily frank, funny, incisive, and

insightful about the studio system in which she rose to stardom. It’s a wise

and juicy book; Crawford has a lot to say about the people she worked with—some

of it deliciously catty, as, regarding Bette Davis: “I resent her—I don’t see

how she built a career out of a set of mannerisms instead of real acting

ability. Take away the pop-eyes, the cigarette, and those funny clipped words and what have you

got? She’s phoney, but I guess the public likes that.”She also explains how, by befriending a cameraman, she learned how to act

for the movies (“Advice to the young actress: Make the cameraman adore you”);

what the differences were between M-G-M, where she came up, and other studios

(“at Metro we were lucky because Louis B. [Mayer] didn’t believe in the casting

couch routine, so very seldom did any of us go through the beddy-bye routines

that were standard at Fox and Warners and Columbia”). For auteurists, she

explained how silly most screenplays were—she describes a ridiculous scene and

concludes, “that was the crap we got before the director and I went to work on

it.” And here, in a paragraph, she dashes around many aspects of her career,

distilling en route a mercurial set of insights:

I have nothing but the best to say for “A Woman’s Face.” It was a

splendid script, and George [Cukor, the director] let me run with it. I finally

shocked both the critics and the public into realizing the fact that I really

was, at heart, a dramatic actress. Great thanks to Melvyn Douglas; I think he

is one of the least-appreciated actors the screen has ever used. (Where would

Garbo’s “Ninotchka” have been without him?) His sense of underplay,

subordination, whatever you call it, was always flawless. If he’d been just a

little handsomer, a bit more of the matinee idol type, he’d have been a top

star. Funny, but I think “A Woman’s Face” was the reason I won an Oscar for

“Mildred Pierce.” An actor who’s been around a while doesn’t win an award for

just one picture. There has to be an accumulation of credits.

She also speaks at length of her general avoidance of the press and of

interviews—her years of protection by studio flacks who coached her, her sense

that what she has to say is of no interest, and the willed darkness (“there’s a

lot I don’t remember, a lot I don’t want to remember”). It’s a splendid book

that cries out to be returned to print.

The over-all point? The profession of the actor is a strange one: for all

the talking and all the expressing that’s done, the words spoken aren’t usually

the actor’s. The emotions evoked are those of the characters, as guided by

script and direction. That’s why this book—and filmed interviews, such as the

unrivalled one of Marlon Brando by the Maysles brothers—are such treasures.

Joan Crawford was great in her roles; some of her movies are among my all-time

favorites (including, of course, “Johnny Guitar,” which she maligned, and

“Daisy Kenyon,” of which she said, “If Otto Preminger hadn’t directed it the

picture would have been a mess”); but the one role she never had in a movie was

the one in which she spoke as she does in this book. And movies in which actors

give voice to their own natures and thoughts, are, for obvious reasons,

unfortunately rare.

The

Other Side of My Life, by D. Gary Deatherage The

Other Side of My Life, by D. Gary Deatherage

Reviewed

by Stephanie Jones (July 2006)

- 1/2

of

5

- 1/2

of

5

"The

Other Side of My Life" is the 1991 autobiography of Joan Crawford's

fifth child (the four "official" adopted kids being Christina,

Christopher, and twins Cathy and Cindy), who was only with Joan

for five months in 1941 before his unbalanced natural mother reclaimed

him. (In the '60s and '70s, Joan continued to mention her "five

adopted children" in several TV interviews.)

Author

David Gary Deatherage was born "Marcus Gary Kullberg"

in Los Angeles on June 3, 1941, the result of his married mother's

affair with a neighborhood Sicilian liquor-store owner. Mother Rebecca

decided in her 7th month of pregnancy to confess her affair to her

husband and then give her baby up for adoption.

The

adoption was arranged through private baby broker Alice Hough and

Joan picked the baby up at Hough's home 10 days after his birth,

renaming him "Christopher Crawford." After press stories

about Joan's new adoption revealed the baby's birthdate, Rebecca

figured out that Joan was the adopting mother and decided she wanted

the baby back. She began a harassing letter campaign to both Joan

and MGM, threatening suicide if her son wasn't returned to her.

A disguised Joan, along with Hough, returned the baby to his mother's

house shortly after Thanksgiving 1941. (Author Deatherage is

circumspect about his birth mother's efforts: "In the end it

came down to extortion. Rebecca never admitted it, but I think she

and Kullberg [Rebecca's husband] had always figured I was a meal

ticket. I'd bet she really didn't count on Joan Crawford returning

me---that she'd receive some kind of compensation to keep her mouth

shut. I was a valuable commodity during my days with Crawford. When

I became 'returned merchandise' my value plummeted. My life was

close to worthless, and as far as Kullberg was concerned, I was

a liability and a candidate for the next life.")

The

year following his return was hellish for Deatherage. According

to what his sister later told him, Rebecca's husband was both emotionally

and physically abusive, refusing to allow the baby in his sight

(the child was kept in closets when his father was home) and, finally,

throwing him against a wall, rupturing the baby's hernia. At that

point, Rebecca gave him up for adoption a second and final time.

(Though her pursuit of Joan and her son wasn't yet finished: In

December 1944, when the press reported Joan's adoption of the second,

completely unrelated Christopher, Rebecca forced her way into

Joan's home insisting that this baby was also her son; she

was arrested and subsequently placed in a psych ward for several

months.)

While

Deatherage here gives a complete account of his tortured earliest

years (most memories supplied by his sister), they're by no means

the sole focus of the book. Rather, as an adoptive child, this

is primarily the story of his search for his roots. The Joan-chapter

of his legacy is mentioned on perhaps 20 pages, with the rest of

the 218 pages devoted to his equally interesting adult interactions

with his God-obsessed itinerant natural mother (whom his siblings

warn him about), his proper Sicilian natural father, his multiple

siblings, and his loving and stable adoptive parents.

For

purposes here, though, the Joan-related items are the most interesting:

Deatherage meets with Christina Crawford (whom he describes as "radiant"

and "much prettier in person") at her home and asks if

he might have changed Joan: "It would have made no difference,"

retorts Christina. "My mother especially despised males....Just

be thankful you were spared." On the other hand, he contacts

Joan's secretary Betty Barker, who tells him, "I think you

would have loved being Joan's son!...All you had to do was be a

good human being, and I know you are, so I know you would have gotten

along with her beautifully." He also quotes a Barker letter:

"When she lost you, all of us were afraid to mention your name

to her for years, as it was a tender subject with her. She would

have loved to have known what happened to you...She always used

to say, 'I had five children, but had to return one to his natural

mother.' She always seemed to feel that you were hers too." Twins

Cathy and Cindy tell him, via phone conversations, that Joan

mentioned him frequently.

In

this book, Deatherage says that while---given his feisty personality---he

probably would have argued with Joan and had a hard time as a kid,

his one regret about his past is that he was never able to meet

Joan when he was an adult. His take on her parenting skills: "From

what I can tell, she had some good intentions. However, her consumption

of alcohol and work pressures often short-circuited those intentions.

She had come from poverty and had worked hard for her rise to fame

and fortune. Why should her adopted children have it given to them

on a silver platter, without blood, sweat or tears?"

Deatherage,

who seems to have turned out to be a well-adjusted, successful person

(thanks probably to his kindly eventual adoptive parents), here

gives a thoughtful, well-balanced account of every aspect of his

sometimes-scary journey toward discovering his past. A fascinating,

recommended read, not only because of the Joan aspects.

Movie-Book

Reviews

The

Duke Steps Out Not

Too Narrow...Not Too Deep

(Strange Cargo) Old

Clothes

The

Taxi Dancer

The

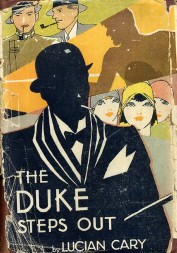

Duke Steps Out The

Duke Steps Out

Reviewed

by Tom C. (July 2022)

-1/2

of

5

-1/2

of

5

The Duke Steps Out by Lucian Cary

(1929, Doubleday) is a typical

love story. The leads are Duke, a champion prize fighter raised on the

mean streets of Hell's Kitchen, and Susan, a college student from one of

Chicago's first families. (Note: In the available synopses of this

lost film, Duke is the son of a rich family who wants to be a boxer.)

Duke

lays eyes on Susan a few pages in and is immediately smitten. So much

so that he hops a train, follows her, and learns she is a student at a

Midwestern college. Duke figures now is a good time for a college

education. He enrolls under an alias, aided by a childhood friend with

connections and (one presumes) a few greased palms. In addition to

Duke's matriculation and wooing of Susan he's also training to defend

his title. (Busy boy!)

The

book has interesting subsidiary characters, moreso on the distaff side.

Minor male characters include Boss Warner and Tommie Wells, Susie's

well-heeled courtiers, who are a tad bland. One could easily see MGM's

male feature players---Eddie Nugent, Nils Asther, etc.--- in these roles.

There

are also Pauline, bored professor's wife, and Norah, a childhood friend

of Duke who found success on stage. Once both reconcile themselves to

the reality that Duke doesn't have the hots for them, Pauline and

Norah fall in with his schemes to win over Susan. (I see Dorothy

Sebastian in the role of Pauline and Anita Page as Norah.)

TDSO

has a Beauty and the Beast vibe, and you know the lead characters will

fall in love by the last page. However, Carey gives the novel interest

by juxtaposing social norms in that Duke leverages his pugilistic

success to refine himself as more than a street-tough brute. He's a

proper gentleman at college, the straightest of straight arrows. Susan,

on the other hand, uses her time at college to cut loose a little,

enjoying everyone's favorite 1920s vices: drinking illegal booze,

kissing boys, and dancing the Black Bottom. But, she's a good girl at

heart, with an independent streak---a more bookish Diana Medford (Joan's

character from Our Dancing Daughters). One can easily imagine an MGM

producer reading this book and envisaging Billie Haines as Duke, and JC

as Susan.

If

you've seen Billie and Joan in Spring Fever, TDSO is the same story,

just replace golf with boxing. Think of it as a Harlequin Romance for

the Jazz Age. If you can hunt down a copy of this book for a reasonable

price, it's good light vacation reading.

A

p.s.: Cary wrote a sequel---The Duke Comes Back (1933)

---which was the basis for two more movies: The Duke Comes

Back (1937) and Duke of Chicago (1949).

Not

Too Narrow...Not Too Deep, by Richard Sale Not

Too Narrow...Not Too Deep, by Richard Sale

Reviewed

by Tom C. (January 2022)

of

5

of

5

I just finished Not Too Narrow...Not Too Deep

(1936, Simon & Schuster), which provides the source material for the 1940 Joan/Clark film, Strange Cargo.The book is a lot different from the film, and for that reason I put it aside

after buying it. However, a trip to the tropics afforded an opportunity

to try again. The differences? For one, there is no Julie (Joan’s

character), which is why I initially dropped it like a hot potato. For

another, Verne (Clark's character) is a lot less likable in the book,

which is narrated by a doctor, Philip LaSalle, who does not appear in

the movie.

The

book focuses on Jean Cambreau, a Christ-like figure. Through his

interaction with the French Guiana penal colony escapees, Cambreau brings them to salvation via

realization that they alone have the power to change themselves. Presumably,

those without such power are doomed to perish in the escape: Moll is

killed off quickly in the book from a snake bite; Verne goes overboard

in a gale; Benet, a child molester, kills himself. The book covers all

three phases of the escape, not just the initial escape: to Trinidad, thence to Cuba, and finally to

South Florida.

One subtle difference---which in post-Code Hollywood could be

only a teensy-weensy bit hinted at, but which is mildly more explicit in the book---is the relationship with the young man, DuFond. In the movie, it is

implied to be with Moll, but in the book, the relationship is with Verne! (Couldn’t have Clark,

whom Joan considered the manliest of men, engaging

in a relationship forbidden by the Code in 1940.)

At

any rate, it is a short novel, and a quick read. I enjoyed the various

ways in which Cambreau led each man to his salvation. The escape

adventures at sea are well told. Happily, mine arrived without the

saucier Harlequin romance-esque cover (at right, above), which would have

elicited skunk eye from the wife! Sort of makes me wonder whether that

version is more faithful to the movie?!

Old

Clothes: A Sequel to "The Ragman" Old

Clothes: A Sequel to "The Ragman"

Based

on the Motion Picture Story by Willard Mack

Reviewed

by Tom C. (August 2021)

of

5

of

5

A

Dickensian

tale at the outset. Tim---Jackie Coogan's character---is made homeless and friendless by a fire at his orphanage. He ends up on the street

and then moves in with Max, a junk dealer who was robbed of $200K (about $3

million in today's money) for

his invention. But, with Tim's help,

Max retrieves his dough after the thieves are brought to justice. Tim and Max promptly spend all that dosh in 2 years and then

head back to the

simple life of the slums. Joan's character, Mary, is a destitute wannabe

dancer adrift in NYC---central casting to Lucille LeSueur (in the movie, billed

as "Joan Crawford" for the first time): You're

wanted on set!---who attempts suicide after (reading between the lines

here) being raped, and who joins Tim and Max after their return to

Skid Row.

The

three form a happy little family, engaged in the business of reselling

old clothes, hence the movie title, living in an old shack made more

homey by Mary's touch. Enter James Burnley, confirmed bachelor---confirmed, that is, until he meets Joanie,

er, Mary. And, really, can you blame him!

Burnley

is smitten with Mary, and hires her to do secretarial work in his

office. Given her history, Burnley must prove that his love is true and

he's not just some rich Wall Street lothario on the prowl for conquest. Burnley initially

invites Mary to his country camp (in the wilds of Westchester County!)

to deliver important business documents. As the adventure unfolds, Mary

convinces herself that this is a ruse by Burnley to seduce her, which is

made more reasonable by Mary's past history. So, after delivering said

papers, she runs away---into a raging storm---while Burnley is away,

ever deeper into the wilds of Westchester County. Cue Max and Tim to show up in the nick of time to save her virtue!

Turns out, however, that Burnley really did need those important papers, his

car did really break down, and he's no cad. And, his intentions are

honorable vis-a-vis Mary. A marriage proposal is made, without the need

for Uncle Max or Tim to provide motivation via the proverbial shotgun,

and accepted.

There

are

more than a few differences between the book and the movie (a sequel to an

earlier Coogan film, The Rag Man, also written by

Willard Mack),

insofar as may be gleaned from the Wikipedia, IMDB, and BOE websites,

which makes me suspect the book came first and was reworked to make

the movie. (Editor's Note: From all sources that I found, the book is indeed

only a novelization of the movie.) Another difference between the book

and film is that the book's heroine is named Mary Egan, not Mary Riley as per the

movie, and the book's Egan is fair-haired (which doesn't sound like mid-1920s JC!).

There's no mention of copper stock; in the book, Max and Tim make the

fortune they eventually blow from an invention. There's also no disapproving

future mother-in-law. And the Burnley character is, I'm guessing, replaced by Nathan Burke

in the movie. Factoids learned: Alligator pear = avocado; Singer Building = NYC

building once the tallest in the world.

The

Taxi Dancer The

Taxi Dancer

Reviewed

by Tom C. (May 2022)

-1/2

of

5

-1/2

of

5

The

Taxi Dancer by Robert Terry Shannon tells the story of Joslyn Poe, a

poor Southern girl who seeks excitement and fortune in New York City as a

dancer (sound familiar?). Ms. Poe finds the going tougher than expected

and is soon down to her last few dollars with the rent looming. Her

tenement neighbor Kitty takes pity on the young Southerner and shows

Joslyn how to extract free grub from eager guys. If you've seen the

streetwise Opal in 1934's Sadie McKee, who takes Joan under her wing, Kitty emits a similar vibe.

When

Kitty is near death from drinking tainted hooch, to raise the money for

a doctor Joslyn resorts to being a taxi dancer. Back in the day, a taxi

dancer would dance with clients for a price, say two bits for three

dances. The house, which furnished the venue and music, took its cut and

the dancer kept the rest. Taxi dancing was generally considered a

salacious occupation given the perception that the dancers supplemented their

income in other ways.

Ms.

Poe, however, soon has a quartet of rich, eligible gents vying for her

attention, including James Kelvin, famous movie actor; Lee Rogers,

independently wealthy doctor; Henry Brierhalter, Wall Street tycoon; and

Stephen Bates, rich dude.

[After various arguments

over Joslyn, she] has a

breakdown, escapes, and goes through typical old-school malaise --- ague,

consumption, pleurisy, the vapors, who the heck knows! When things seem

darkest, Rogers declare his true love for Joslyn, which rallies her.

I

find it interesting that in the pivotal early period of JC's career MGM repeatedly went back to her dancer persona ---

as chorus girl Bobby

in her first credited role in Pretty Ladies

(1925),

as chorine Irene in her first major part in Sally, Irene and Mary (1925), and of course as the quintessential flapper in her breakout role as Diana Medford in Our Dancing Daughters (1928).

The Taxi Dancer (1927)

was Joan's first starring role and is in keeping with the

dancing-girl-makes-good theme of her early film career. The scant

available evidence is unclear on the success of the movie --- the most I have

found online seems to range from lukewarm to positive, but Joan did not

star in most of her next few, although she was the

female lead to MGM's top male stars until ODD put her firmly on the path to stardom.

The

Taxi Dancer is a light read. Think of it as a 1920s Harlequin romance.The book seems to differ from the movie insofar as one may glean from the

film that Rogers is a medico and not a dissolute card sharp. Also,

Brierhalter seems more evil in the book. Oddly, the notices I've read

about the movie seem mixed, with some giving the lead's name as Joselyn,

although in the book it's spelled Joslyn (sans "e"). One may argue that

the portion of the novel that strains credulity the most is that all

these successful Big Apple sophisticates instantly go mad for our

Southern belle. From the few precious minutes of the film that we have

from the TCM documentary on Joan, she looks lovely as Joslyn Poe, so who

knows---maybe her looks and a cute Southern drawl did the trick.

One

can easily see JC sinking her teeth into this role, given the similarity

in the back stories of Joslyn Poe and Joan Crawford. Indeed, she says

as much in the book “Conversations with Joan.” Likewise, one can easily

see an MGM producer like Harry Rapf reading this book--- which was widely

serialized in newspapers (an MGM strategy to drum up PR for their

upcoming movies) --- and thinking it would make a good vehicle for the

erstwhile Lucille Le Sueur.

If

you can find a rare copy of the book, it's worth a quick read for the

dedicated Joanephile. All in all, I would much rather see the movie,

though! The short snippets available online seem to be in good shape. So

who knows? With the recent restoration and release of Sally, Irene and Mary ---

Joan's first significant role --- and the imminent lapse of the movie's

copyright after 95 years, maybe someone out there will bless us Joan

fans with a release of the Queen's first starring role. Such is my

prayer.

The

Taxi Dancer The

Taxi Dancer

Reviewed

by biblio.com

(seller: ReaderInk) (year unknown: 2000s)

This novel about a rural Southern girl, trying to make it in on her own

in New York, who can only find work as a paid dancing partner in a

"dancing academy" -- which leads to her getting involved with

(successively) a gambler, a dancer, and a millionaire -- was first

published as a syndicated newspaper serial beginning in May 1926. M-G-M

knew surefire movie material when they saw it, and by the beginning of

June it had already been synopsized by the studio's story department; a

full scenario was completed by September, and the resulting movie was

ready for release by the following March. It was the first film in which

a young Joan Crawford received top billing (it was early enough in her

career that at the time the story was acquired by the studio, she was

still being carried on the payroll under her original name, Lucille

LeSueur). It may not have been entirely coincidental that Crawford was

cast in a role in which dancing played such a central part: according to

many accounts of her career, frustration at her lack of progress

towards stardom under her early M-G-M contract led her to embark on her

own self-publicity campaign -- a major feature of which was entering

(and winning) numerous local dance competitions. The film may have been a

major career boost for Crawford, but for the studio it was just a

programmer: her co-stars were undistinguished, ditto the director (Harry

Millarde, then at the tail end of an unremarkable career), and the

movie was clearly not important enough for the issuance of an

accompanying "photoplay edition" -- so apart from its original newspaper

serialization, the only other time this novel appeared in print was

four years after the movie, in an edition by the minor publisher Edward

J. Clode, of which this A.L. Burt edition was a cheap reprint. (And just

so we're clear: this is *not* a photoplay edition, and in fact makes no

reference at all to its earlier publication or to the existence of the

movie; I guess it's possible there was some link to it provided on the

dust jacket, but alas it ain't here.) So when you look at the entry for

the film in the AFI Catalog, and wonder how a 1927 movie could have been

based on a "1931" novel -- now you know. Oh, and by the way, the book

in any edition is quite scarce: as of this writing, OCLC records only three institutional copies of the Clode edition, and just two of the Burt printing.

|

Starring

Joan Crawford: The Films, the Fantasy, and the Modern Relevance

of a Silver Screen Icon, by Samuel Garza Bernstein

Starring

Joan Crawford: The Films, the Fantasy, and the Modern Relevance

of a Silver Screen Icon, by Samuel Garza Bernstein

The

Duke Steps Out

The

Duke Steps Out

Old

Clothes: A Sequel to "The Ragman"

Old

Clothes: A Sequel to "The Ragman"