All that's left of the flamboyant Hollywood of old is Joan Crawford, who still wears $10,000 fur coats, gives leopard skins for presents, and otherwise acts the way big stars were supposed to act. "But," she hastens to add, "you should see me scrubbing my kitchen floor." In an Adrian original, of course.

by Cameron Shipp

Originally appeared in Cosmopolitan, April 1951

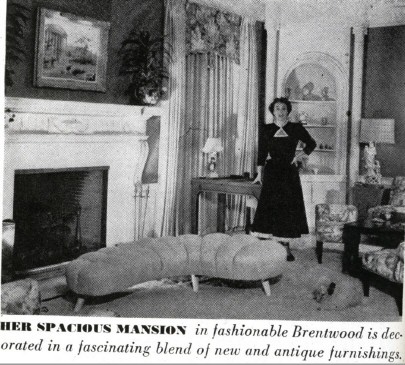

Miss Joan Crawford, the movie stars' own movie star, lives in a twenty-four-room luxury mansion at 426 North Bristol Avenue, Beverly Hills. The great house was designed for fun and comfort when Miss Crawford, during her early twenties, was earning nine thousand dollars a week as queen and darling of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, biggest studio in the world, and it represents--from the private theatre overlooking the swimming pool to the white-columned boudoir--about all the domestic delights a rich and famous lady can command.

For several days early last summer, this house rattled and strained with high-octane emotion and feminine despair. Closet doors were slammed, drawers were yanked, and the nervous stop-and-go of high heels stabbed uncertainly at the thick-as-cream carpeting from bar to bedroom. And there were fervent imprecations.

The cause of all this frustration and woe is now known by the Crawford secretariat as the Case of the Missing Filing Cabinet. It was a bad time, and neither Miss Crawford nor her aides has ceased to shudder about it.

The filing cabinet contained some fifteen hundred names of Joan Crawford letter-writing fans. No other motion picture star would have bothered to look at them, let alone file them and dote on them, but to Miss Crawford a letter writer is a jewel, a cupcake, a sister-under-the-skin, a human being whose dignity must be protected at all costs. "By heaven," she says reverently, "if my fans can write me, I can answer 'em." The addresses never were found, and Miss Crawford, who will go to any unreasonable length to please a fan, was compelled to labor from sheer memory to answer admirers who, after twenty years' intimate thralldom, now neglect to set down their return addresses. The ardor of Crawford fans, a special kind of ardor possibly not equaled by any other star's, is actually overmatched by Miss Crawford's passion for them. This passion is both sentimental and calculating: emotionally, Joan is as responsive as a strange and grateful child at a birthday party; at the same time, she is as professionally competent as a slide rule. And there you have it. Add the red hair, the big blue eyes, and the imaginative flair, and you've got yourself a movie star. No actress living works harder at her job.

Joan Crawford occupies a unique position. She is, although she deplores the suggestion, the last of her fabulous line, the last of the great movie stars of a free and fancy era, and though she tries to do everything possible to dispel that notion, she still behaves in character.

When pinned down, she hoots at the idea that she is either movie-starrish or that she lives glamorously.

"Should have seen me last night, " she says. "Should have seen me scrubbing the kitchen floor."

It's a fact. There are numerous witnesses willing to swear on a stack of Hollywood Reporters that they have personally observed Crawford on her hands and knees scrubbing the floor.

But Henry Rogers, her press agent for many years, observed gently: "Yes, dear, I saw you do it. And you were wearing an Adrian original."

Yet after spending every instant of her adult life in professional pursuit of glamour, Joan is immune to paradox. As a result, it sometimes seems that she is incapable of making the simplest gesture without laying herself open to accusations of playing to the gallery. Having many detractors, she is often falsely accused, but also she deceives herself.

A few years ago she came to New York to make personal appearances and attend to publicity chores in connection with the opening of one of her pictures at the Capitol Theatre. As usual, there were long lines of fans stretching out from the ticket window before seven a.m., formed by girls who came early merely to be first to see her new picture.

Such devotion naturally impressed Joan. "I'd like to see that," she said. When word was passed to the manager of the theatre, he blanched. "Not a chance. You want us to have riots? Keep her away from here."

Joan insisted. "I'll slip in from your office," she told him, "and huddle down. In disguise," she added.

And so she prepared herself. She fluffed out her hair. She put on a simple black four-hundred-and-seventy-dollar dress. She pinned a gardenia to her handbag. She selected a rhinestone ring the size of a biscuit, and she shrugged on a ten-thousand-dollar lynx coat. "Little cold out," she apologized. To complete her anonymity, she clapped on a pair of dark glasses, and then she sallied forth.

"You'd have recognized that silhouette, those square shoulders, eight miles away in a London fog," one attendant swore later.

The result, of course, was a gratifying outburst of pandemonium nine seconds after Crawford hove in sight. Joan was tearful with appreciation, gallantly signed all autograph books thrust at her, waved happily from a taxi for three blocks after police rescued her from the crowd, and was innocently puzzled because her disguise plan hadn't worked.

Today, Joan not only makes no effort to conceal her identity when she goes out in public, but considers it her bounden duty to appear in full regalia as a movie star. So far as that goes, she has never presented herself even on her own studio lot in anything but her best; she looks with wonder and dismay on newcomers who show up in butt-sprung slacks and careless coiffeurs, and as for stars so disdainful of public opinion as to appear disheveled on the street, she considers them not only idiotic but somehow dishonest.

"You do owe your public something," she says.

Joan moans over the misguided Van Johnson, who once attended one of Atwater Kent's chi-chi parties in a dinner jacket and bright-red socks. She thinks he merited the rebuke of an old-time player who scolded him with: "You aren't famous enough to dress like that, Van. And when you are--you won't."

Joan's swooping appearances in the shops and restaurants of Hollywood and environs are made from a regal black Cadillac, which she drives herself as if all highways were private roads. Beside her sits Cliquot, a white French poodle, clipped like a clown and powdered like a fifteenth-century courtier. Cliquot wears either a red or green jacket, initialed "C.C.," and carries a handkerchief in his pocket. He places one manicured paw on Joan's arm as she drives and takes an amiable, proprietary interest in everything.

The wardrobe that backs up the Crawford public appearances--and the private ones, too, for that matter--is as extensive and as special as any goggle-eyed boarding-school debutante might imagine in her brightest dream of wish fulfillment. The legend is that Crawford, who has always been partial to furs, owns thirty-five prime examples of beaver, mink, karakul, lynx, and broadtail. Joan, who swears she has not purchased a new fur for more than two years, denies this, but when a male reporter was recently allowed to cast a bedazzled eye over Joan's effects, he counted twelve coats in one closet, all in the ten-thousand-dollar class.

Her dressing room, which is all white with tall, chaste columns, is large enough for a beauty salon with specialty shop attached. It is surrounded by deep, wide closets, and the passageway from her sitting room is equipped with closeted shelves on which repose enough alluring equipment to stock a smart shop. Shoes are racked in groups of twelve on shelves eight feet high. Evening gowns here, dinner dresses there, afternoon frocks here. Like all smart women, Miss Crawford is a devotee of the "little black dress," which can be worn anywhere, and she has them by the dozen. Most of them are by Adrian, who won't touch a hemline for less than five hundred dollars, but others are by Joan's new designer, Sheila O'Brien, whom she discovered, and who now creates clothes for movies.

Jewelry is another item Miss Crawford collects with magnificent abandon. One of her main spectaculars is a diamond ring in a modern, flaring setting, designed by Andre Fleuridas. The stone is the size of an air-mail stamp. It gleams with wicked shafts of chill blue and sinful flashes of scarlet and was a wedding gift from Franchot Tone. But like her diamond clip, which is as big as a child's hand and resembles a cluster of icy flames, and her thick amethyst collar, the big gem reposes almost exclusively in a bank vault. The amethyst collar is so heavy Joan says she feels like a Salem witch in the stocks when she wears it.

"Or like an ox pulling a cart. But, boy, I'm willing, I'm willing!" she says. A replica (repeat, replica) of this collar cost another girl ninety-five hundred dollars.

In spite of the fact that her jewels-in-chief are seldom seen, Joan always appears at parties as gleamingly gemmed as a presentation sabre. Her earrings would make a television star gasp, and her bracelets shimmer from wrist almost to elbow. Her necklace, usually a simple band flashing with more than a hundred diamonds, looks like the kind of bauble an emperor might give an empress.

All this finery, which Miss Crawford wears as casually as if she certainly did know the emperor, gives the lady a good deal of merriment.

Recently, at a swank soiree, she was decked out like Tiffany's front window and flashing like a lighthouse. Nancy Sinatra made appropriate "Oos" and "Ahs" over the showpieces.

"You like these?" asked Joan, touching an armful of bracelets. "Here, let me give them to you."

Mrs. Sinatra backed away. Obviously Miss Crawford was either madly touched in the head or she was guilty of the bleakest bad taste.

"Why, I gave one to Reggie Gardiner's wife just the other day," said Joan.

"Joan dear, you know I couldn't possibly. Why, those are fabulous--"

"Great jumping scott, Nancy!" exploded Miss Crawford. "Do you think they're real?"

As Joan will happily explain if given an opportunity, the Crawford display-purpose pretties are as phony as Prince Michael Romanoff's genealogy. She seldom gets the opportunity to explain because her movie-star reputation is so firmly pinnacled by now that no one but Monsieur Fleuridas would ever suspect she was not wearing Grade-A carats.

In addition to such generous gestures as offering to give away costume jewelry, her equally uncontrollable habit of giving away real jewelry and big automobiles to people she likes has cost Our Heroine many tears. In a swank colony whose members, despite their fresher youth and beauty, are constantly outshone by a star some of them worshiped when they were boys and girls, a certain amount of vindictive jealousy is inevitable. Joan gets more than her share of it.

She went to a party at Cesar Romero's house not so long ago. Being between husbands, Miss Crawford was somewhat embarrassed about making her entrance without an escort, but as Mr. Romero himself, an old and dear friend and favorite dancing partner, was to be her date for the evening, and as there were to be other motion-picture actresses present, some of them internationally famed beauties, Joan innocently decided to do Romero proud and give everybody a show for the money.

She did herself up in a white evening gown cut low enough to suggest the tender glory of her thirty-eight-inch bust, and she put on the icebergs. As is her custom, she arrived very late.

To her left sat a group of actresses. Three of them were friends for whom Crawford had done important favors, but on this occasion they might as well have been caldron brewers out of "Macbeth." "Get her!" Joan heard in one of those whispers carefully calculated to be overheard. "My Gawd, our queen!" said another glamour witch. They proceeded to rip Miss Crawford apart, from toe to tiara and to hell and back, in carefully modulated, pseudo-British accents.

Crawford stood it for not more than ten minutes. Without greeting Romero, she turned and fled. She went home and bawled.

A lady who was there offers an opinion. "She came as a movie star, and she out-movie-starred 'em," she explains. "The others were trying to movie-star it, too, but man, when Crawford comes on, the little girls might as well scram. She's it."

In the past--say, fifteen years ago--it is undeniable that Joan committed certain gaucheries. She thought, when she acquired her great house in 1929, that real people did things the way film people did them in the movies. She stationed a butler behind every chair--but only once--before she discovered that such display was considered flamboyant, even in Hollywood. Once, when a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer press agent pleased her enormously, she sent him a Christmas card that staggered him. The press agent, a not-too-well-paid writing man, lived in a one-room flat in a modest section. He and his neighbors were understandably flabbergasted when a fabulous twelve-foot leopard-skin couch arrived with Miss Crawford's card.

Today, the Crawford flair for extravagant gifts blossoms chiefly at Christmas. She starts buying early in July, and she neglects no one. She does her own shopping and is lavish in the purchase of sports coats and watches. If possible, she has everything initialed. She sends cases of champagne to the gatemen and cops at Warner Bros. Studio, where she is now employed, and does up special and expensive favors, from jewelry to perfume, for wardrobe women and hairdressers. Nowadays, she is the only star who closes every picture with a party and a present for everyone.

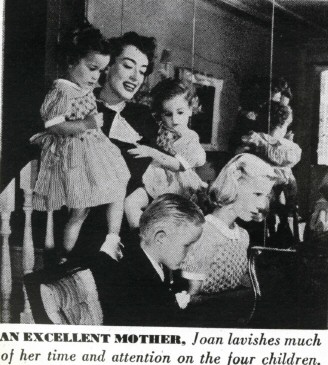

All this gift-giving turns out to be, when examined honestly, neither bad taste nor entirely public relations. Joan's exuberant pleasure in generosity, plainly inspired by her yearning for fine things during a girlhood of poverty, is far exceeded by her delight and pride in receiving gifts of any caliber, even Christmas cards. She has four adopted children: Christina, eleven; Christopher, eight; and the twins, Cathy and Cynthia, who were four last January. She inundates them with Yuletide presents, and they, in turn, shower her with loot. Many stars leave home for the holidays and spree at Palm Springs or Las Vegas, only Crawford, sentimental actress and professional movie star to the last gasp, behaves as if she had copyrighted the Christmas tree.

On the other side of the picture, Joan's extremely generous private charities have never been fully exposed--and will not be here; they seem to be the only phase of her life about which she is not invariably forthright. It was learned only recently that she has for many years supported an expensive ward at Hollywood's Presbyterian Hospital, and that a well-known Hollywood doctor, known as "Bill" by most of the colony, has carte blanche to use it for the needy. And this is the first time the fact has ever appeared in print that Joan is the anonymous donor who does certain remarkable things for a number of poor families every Christmastide.

At the peak of her prowess at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, before she left there in protest against exclusively clotheshorse roles, Joan made nine thousand dollars a week. Now, at Warner Bros., she gets two hundred thousand dollars for one picture a year, and is permitted to make films at will at other studios. But in fashion with all wage-earners today, especially the big ones, Joan vehemently denies that she has a florin to her name. But because she pays ten per cent to her agent, Music Corporation of America, is in the ninety-per-cent income bracket, has a large house, four children, a staff of servants, and a professional wardrobe to support--it is highly probable that Miss Crawford has not been able to stow away many greenbacks. This bothers her not at all. She considers herself a working girl and is happy to be among the employed. Because she devotes herself to the children, constantly coaching them on how to curtsy and say "sir" when introduced, and sitting up with them all night when they have the smallest childhood disease, Joan today has little time for the routine of Hollywood social dazzle.

"But I miss dancing. Lord, how I miss dancing!" she says. She is, of course, one of the most accomplished steppers in Hollywood. She came here from a Broadway musical, "Innocent Eyes," won every possible cup offered for Charleston contests in the twenties, and has danced expertly in many films. But proper escorts are few for a Crawford, and Joan thriftily makes public appearances only when an appearance might do some good and, possibly, bemuse a fan.

The big house at 426 is a kind of symbol to Miss Crawford. She adores it and shines it personally. Few servants can keep up with her; she changes them almost as often as she changes her bed linen. She began 1951 with neither a butler nor a chauffeur. Nurses and maids apparently arrive and leave on the hour, every hour, but a nucleus of faithful retainers, headed by Mrs. Margaret Colby, her chief secretary, remains year in and year out. Two special secretaries handle fan mail, and swamp the post office with large envelopes containing Crawford pictures. (No niggardly three-by-fives from Crawford: if you ask for a picture, you get it full size; if you are a special admirer, you get an eleven by fourteen. As Joan does all this at her own expense, her studio rejoices. She is among the top ten fan-mail goddesses at Warner Bros.)

As the prototype of her kind, Joan is an engaging sight on the set. She arrives at six a.m. and, if an attendant is not on time, is capable of raising a ruckus that reverberates to Jack Warner's office. Cliquot, the poodle, is in attendance. So is Mrs. Colby, the secretary, to whom Joan dictates between scenes; Gertrude Wheeler, hairdresser; Eddie Allen, makeup man; Elva Hill, wardrobe woman; and Sylvia LaMarr, stand-in--all front and center, right at hand. Two days after her arrival at Warners in 1943, Joan was able to greet every assistant director, grip, electrician, and messenger boy by his first name; today she knows the names of their children.

Recently a shy publicity man approached the Crawford set with a group of twenty-five visitors in tow.

"Is it all right? Will Miss Crawford mind?" he inquired.

"Mind? Brother, bring 'em in. Got a tough scene. Just what she needs."

Turned out that way, too. In front of the fans, Joan ripped off the work in one take, and then waved gaily to everybody.

But on the day forty members of the Sadler's Wells ballet troupe came in, Joan blew higher than a March kite and piteously begged director Vincent Sherman to make some excuse for her. Before the professionals, she said, she felt like a fool.

She does not share the usual Hollywood ambition to star in a Broadway play. Not for love, fame, or money. "I'd die. I'd petrify. I'd be scared to death. I'm a motion-picture actress. I don't know anything about projecting to an audience." Radio appalls her, too. On her infrequent appearances, she pays four hundred dollars out of her own pocket for the privilege of making transcriptions, or tape recordings, to escape the horror of working before an audience. Joan knows what she is--a movie star--and though television intrigues her as a possibility, she is frankly wary of anything that is not strictly her own medium.

On the set, Joan is gay and friendly, but when she blows up, she blows high. During the making of "Harriet Craig," she insisted to Vincent Sherman that his direction of a certain scene was false and dishonest.

Joan took her case to the rafters, and yelled up a shrieking tantrum.

She did it her way, then called the whole staff together, more than seventy-five people, and apologized. She wept and abased herself. She said Mr. Sherman was a great director and that she respected him and that she was all kinds of a temperamental idiot. The staff loved her for it.

The scene was printed the way Joan wanted it.

On the same set, a visiting celebrity had the gall to call a photographer to take a picture of the visitor with Cliquot. Joan got wind of this instantly, summoned an assistant director, and announced in sharp syllables that such a trick was presumptuous. The pictures had to be torn up. But any reasonable facsimile of a human being can easily get his or her picture taken with Crawford herself. In fact, Joan is the only star who permits fans to make a habit of staying on the set all day while she is working. Three of them, Betty Barker, lee Kern and Helen Fullerton, regularly spend all day Saturday with her, then drive home, with Cliquot, in Joan's car. At any hour of any day there are likely to be be three or four of these faithful ones at the house, ready to run errands or lay down their lives.

When Joan reported to Warner Bros. in 1943 at fifty thousand a year (an embarrassing cut from her swollen Metro stipend) she rejected the first four pictures offered to her, then voluntarily took herself off salary because she wasn't working. This period was one of immense distress during which she was considered "box-office poison." She held out, however, until Jerry Wald offered her "Mildred Pierce" which she recognized instantly as her apple. This film won her the Academy Award for 1945, over Greer Garson, Jennifer Jones, Ingrid Bergman, and Gene Tierney. On the night the Oscars were presented at Grauman's Chinese Theatre, Joan dominated the proceedings by being absent, thus garnering thrice as much attention as if she had appeared. It was considered a typical Crawford trick, but the fact is that she was in bed with a temperature of 104 degrees. It goes to show: Crawford can't even get a cold in the head without acting like a movie star.

Today she reads between three and four hundred scripts, scans between two and three hundred synopses, and hurries through at least seventy five novels a year in a hopeful effort to equal "Mildred Pierce."

"Should I keep on doing the Cinderella story?" she asks seriously. "Do I always have to be the shop girl from the wrong side of the tracks who marries the boss's son and learns how to order the wine? Isn't there some other story for Crawford? Couldn't I do a musical again? Or a comedy? I'd like some variety."

"Closest I can some to saying what I want is this: something to make 'em talk. That's why I do an off-beat part now and then, or do my hair in some extreme manner. Keep 'em talking!"

The celebrated Crawford glamour is now something that Joan takes, if not casually, at least in stride, as an insurance man might regard his special knowledge of trick clauses in fine print that nobody else comprehends. These days she is more personally concerned with her children, whom she loves strenuously. Glamour is a profession to Crawford, so much so that she virtually disdains it. Asked how she keeps her figure--she is five feet four, weighs a steady 110, and has a twenty-six inch waist--she replies:

"I keep house, I usually have a baby on each hip. And when I reach over to pick things up, I don't bend my knees. I used to swim a lot, but not now. Don't have time. But I'm lean and flat in the hip. Here, feel that."

Miss Crawford offered a hip to be felt. Your reporter, no fool, felt it appreciatively. She was right.

"Glamour? Nonsense," Joan insisted. "I think people appreciate actresses more as human beings today. At least, I think that's how my fans appreciate me. I don't live glamorously. I didn't even have a cook in the house Christmas Day. Still...I have a dinner date in fifteen minutes. Now if you want to see how it's done--"

Joan at that moment was scrubbed and burnished; her short red hair was severely in place. But she wore no make-up. She was handsome, but not beautiful.

"You time me," she said as we went into her mirrored and columned dressing room.

Starting from scratch, she applied a thin base of powder to her cheeks. She put cream on her nose to make the powder stick there. She did her eyebrows in no more than four swoops of the pencil.

Then, with great concentration, she put mascara on her eyes. She reddened her mouth, first with a little finger, then with a brush. Then back to the eyes, the first application of mascara having had a chance to dry.

When she looked up--well, there was Crawford. Her eyes were twice as big. Her mouth provocative. It was the million-dollar movie-star face you have seen on a thousand screens.

Time: precisely eight minutes.

"You have to know how," said Joan. "Didn't spill anything, either. Now--"

At this point, your reporter departed.

"Don't you dare say I look like a movie star or live like a movie star," Miss Crawford called after him.