Life Is For Living

A Multi-Talented Star, Joan Crawford Works for Charity, and is a Business Woman Too

by Roberta

Ormiston

Originally appeared

in Lady's Circle, May 1972

Joan Crawford, when I phoned her for an appointment for this story,

said, "Give me an hour with my secretary. Be here at 10:30. All

right?"

Joan Crawford, when I phoned her for an appointment for this story,

said, "Give me an hour with my secretary. Be here at 10:30. All

right?"

Here was her apartment, its 28th-floor windows uncovered to the drama of Manhattan's roof tops and sky; the oyster white under-curtains and egg-yolk yellow over-curtains pulled back as far as they would go.

Like the L-shaped livingroom and the dining room, the long entrance hall, lined with white bookshelves, is an expanse of dark square parquetry. The sofas and chairs are white, some with a trailing fern pattern, yellow or bright green, like the round pull-up stools that flank the two large coffee tables. Against one wall teak shelves hold up the curios Joan and her late husband, Alfred Steele, brought home from all over the world. The modern yellow dining-table is surrounded with little open armchairs of bright green, yellow and white. And the broad window still holds beautiful Bohem birds, glass-domed.

Only in Joan's bedroom do the colors change. Here pink curtains over white are drawn back to another panorama of skyscrapers. Before this window stand a small round table and two chairs, for breakfast or tea. The headboard of Joan's queen-sized bed is quilted, white with large pink flowers. A small room next door has been turned into her dressing-room. Cupboards in which clothes hang at two levels reach to the ceiling. A big white dressing table with a large lighted mirror stands before a small armchair. It's a practical work room, without a frill.

All over the apartment are masses of high green plants and big bowls of gay-colored flowers so that, despite the views from the windows, you think of California.

On my arrival Joan, who had managed a shampoo after working with her secretary, came towards me, arms outstretched. Her hair was wrapped in a white Turkish towel fastened with a giant-sized safety pin. She wore a Chinese damask robe of the blue Hollywood calls "Crawford blue," a little lighter and softer than Wedgwood. Beneath its soft folds her bosom was firm and high. The big round lenses of her glasses were tortoise-framed. Her yellow thong sandals showed toenails, like her fingernails, of the palest pink. Her pale brown freckles showed -- for she wore not one smidgen of makeup. Her body and facial bones, however, suggested that she'd just escaped from a Greek frieze, incredibly lovely!

|

| Miss Crawford as hostess to settlement house children. |

Leading our way to a room adjoining the livingroom she said, "We'll talk in Mama's room, so we won't be disturbed when they come here to set up the radio equipment."

Mama is short for Mamacita, Joan's personal name for her personal maid, who is not Spanish, as you might expect, but German.

As we settled ourselves in the low green and white chairs that stood against this room's one colored wall, a dark lime green, she explained, "I couldn't let Mama live in what is called a maid's room in this apartment house. It's so small I've turned it into a walk-in shoe closet."

The 23 radio tapes on which she was going to work that morning were her last scheduled job as 1972 Chairman of the American Cancer Society. "I've finished the TV slots and the speech that's to go out to the crusaders in 26 cities. It's the beautiful speech it has to be. I had a writer do it for me."

She believes in pro's, has always. Years ago, determined to erase her native San Antonio, Texas accent from her speech, she worked with opera star Rosa Ponselle's coach. When she decided the time wasted on movie sets was idiotic she took knitting lessons. "With my hands busy," she explains, "I found I could concentrate harder on what everyone else and I had to do."

She reached to a high closet shelf for the last afghan she'd knitted, a soft wool of soft blue-lavender, lined and bound, saying "Alice Maynard here in New York does my binding."

Joan is meticulous about proper credits and as a result makes introductions where most people wouldn't bother, always enunciating names so everyone knows what to call everyone else.

"When I began to hook rugs I had more lessons," she said, carefully folding the afghan back into its big box. "And more lessons when I became interested in needlepoint."

I asked if she had found her handiwork therapeutic when Alfred Steele died. She shook her head. "Nothing that let me think would have been any help! What I would have done without Pepsi-Cola I do not know. I just wanted to work and work, be so tired when I fell into bed that I couldn't think -- and so could sleep.

"The worst thing that ever happened to me, that -- losing Alfred so soon after having found him..."

It was a sad and shocking thing for her, missing her husband in bed beside her, to find him on the floor of his dressing-room. She'd had no inkling that he was seriously ill, only thought he was tired when, in Colorado, he'd fussed because she'd gone rushing from room to room to answer the telephones, warning "Don't run in this altitude!"

Sensing that his protests reflected a weariness in him, she'd had his physician fly out from New York.

"And," she says, "I brought in a whirlpool bath so he could get in it every day, as he had at home. I ordered a massage table from which he used to get up limp and relaxed as a rag doll, all tension gone. Also, I made him promise that after every four weeks of work we would take a week's holiday.

|

| With her husband Alfred Steele before his tragic death. |

Her secretary came in to say the radio man had arrived, and that a magazine was in a great rush for pictures of her at a recent opening of a Pepsi bottling plant. When those of the last opening were suggested, she said, "No, bring me the Birmingham folder. They'll reproduce better."

I had a feeling she had the pictures in all her folders neatly filed away in her mind.

"And, please," she said, "ask Jerry Kornbluth to come in so we can say good morning before he starts setting things up."

In Joan's book, life is for living, living as greedily -- her word -- and as graciously -- my word -- as possible. Looking back over the years since I, then editor of a magazine that ran a contest to rename a chorus girl called Lucille LeSueur, chose Joan Crawford for her -- which she didn't like at first -- I can remember no time when she has forgotten about this.

Once, when I had complained that she was very changeable she told me, "I hope I still am! I wouldn't ever want to stand still!"

Never ask Missy Crawford a question unless you're primed for a straight answer from her!

With her growth, a refinement has come to her thinking, her grooming and her houses. First in the latter was what she, amused at herself, calls "Cocktail Chinese." Next came early American, her hooked-rug period. Then, in violent reaction, she went somewhat baroque. It was with the skilled guidance of Billy Haines, movie star and interior decorator, that she found her way to English Eighteenth Century, which she'd learned to accent with modern and Chinese -- like the paintings, many abstract, that splash vivid color on her white walls and her teakwood shelf of curios. Also Princess Lotus Blossum, half Pekingese and half Lhasa Apso.

Princess, with specks of yellow bows holding back two gray and white locks of Pekingese-Lhasa Apso hair, was very skittery the morning I was there, so skittery Joan asked Mamacita to put her in the dog's little play-pen so she wouldn't be underfoot while the radio equipment was being installed.

I asked Joan, recently voted one of the first of the Ten Outstanding Women in Business -- for her work as a member of Pepsi's Board of Directors and Good Will Ambassador in Public Relations -- where she got her extraordinary capacity for work. "It's the child of my ambition and determination, I guess," she answered, "and my mixture of French and Irish blood. And, probably a behavior pattern I acquired, of necessity, very early in my life.

"By this time everyone must know I washed dishes and made beds and scrubbed floors at two schools to pay my tuition. At 16 I was helping my mother in the hand-laundry she ran. In my 'teens still, when I was in the chorus of the Winter Gardens, after the final curtain, I would go hurrying over to Harry Richman's nightclub.

"Jack Oakie used to walk me home. He was a true friend, and not about to have anything happen to me."

Joan will not accept as stars those who slouch around with unkempt hair, careless makeup and nondescript clothes. "They're personalities," she says firmly. "They do not last, as stars do!"

Undoubtedly she is glamorous, even when she goes around the house without makeup, so her skin can breathe. She will often change her costume four times a day to properly dress for as many occasions. She's meticulous -- ask her devoted Mamacita -- that her hat and gloves are the same pink as a dress or suit, with her lipstick and polish a complimentary pink. Asked about her diet she laughed. "Very simple. I always stop eating when it tastes best."

She would like to do more movies for TV than she has been doing.

"Repeatedly, when I was on tour for my book," she says, "I was impressed at the way TV gets you into people's homes. Many who came to my autographing parties wouldn't have been there had it not been for TV -- housewives, artists, often the wives of store executives and lots of teen-agers. I could tell by the books under their arms that they'd skipped classes to be there. And when I asked how they knew anything about me they answered, 'We see you on TV!'

"If only the scripts were a little better. I have to force myself, often to reach through them so I can explain why I'm turning a job down. Always, too, there's the chance of hitting a jackpot.

"Invariably I'm obliged to make an overnight decision and be ready to fly to London or Alaska or wherever in a few days. They fly me a script in a mail pouch and have it picked up by a messenger. And I sit up until 3 A.M. to finish reading it.

"I'm not always free, of course. Winter for me is the best time for movie-making. In the spring and summer and early autumn I'm pretty well tied up with Pepsi, that being when bottling plants are most likely to open."

She had, she said, seen Christina, her oldest child, in the new TV series about ESP, "The Sixth Sense." "Also," she said, "she recently did a Chevy commercial. A good actress, Christina!"

The twins, Cindy and Cathy, are married respectively to a successful Iowa farmer and the owner of a marina in the St. Lawrence Valley in New York State.

Christina, the twins and Christopher, who arrived between them, are all adopted. They came to Joan as infants, 10 days old.

She doesn't gloom about her children, grown and on their own, being separated from her, not needing her any more. She would not have it otherwise. It means they're self-sufficient and healthy adults now.

She's accepted the honor of being the 1972 Chairman of the American Cancer Society subject to Pepsi-Cola's approval. When the company said please go ahead, promising to work her Pepsi schedule around the Cancer schedule, it was set.

The additional pressure this chairmanship places on her she dismisses with a shrug. "We're all put here to help everybody else."

Joan has often told me she cannot understand women who rule out any experience or emotion likely to bring wrinkles. "That isn't for me! I don't want to look as if I'd been punished by life, but I do want to look as if I'd lived."

She repeats this thinking in her book, "The Way I Live," writing: "All my nostalgia is for tomorrow, not for any yesterdays...There's nothing I regret or would change. If it hadn't been for the pain I wouldn't be me. I like very much being me."

Over the years I've watched her mature into a woman she, with her standards, can respect and with whom she can be friends. No one is likely to be born to this. It is rather something achieved when, like Joan, we never doubt that life is for living.

Take

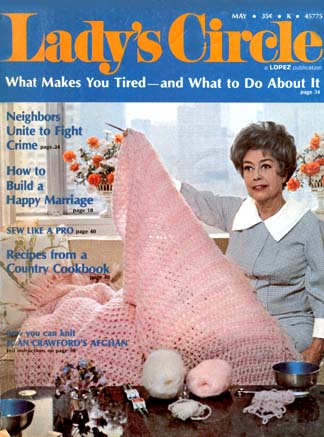

a Tip from a Star -- Make an Heirloom Afghan

by Joanne

Schreiber

|

Her lovely pink-and-white afghan is an Alice Maynard design, and the Alice Maynard shop is one of the oldest and most exclusive needlework shops in New York, with some of the most beautiful designs you've ever seen -- not only in knitted and crocheted items, but in needlepoint and crewel as well. The shop is located on Madison Avenue which is loaded with elegant and expensive shops.

Women who love fine needlework are the same friendly and helpful souls the world over, whether they are in sophisticated New York or casual Kansas. A charming Cuban lady, Miss Otilia Ruz, worked out the instructions for Joan Crawford's afghan, so we could bring them to you. This is very easy -- just a simple garter stitch, but the lovely mohair yarn makes it super-special. The Reynolds yarn called for in the instructions is imported, and a ball weighs in at 40 grams, not ounces. The saleslady in your local yarn shop will be able to give you the American equivalent, if the imported yarn isn't available where you live.

Joan Crawford's Afghan

Size: 54 by 70 inches

Materials: Reynolds #1 Mohair

14 40-gr balls of each 2

colors

#13 circular needles, 36" long

1 size K crochet hook

Gauge: 5 stitches = 2 inches

Work with one strand of each color all the way through.

Cast on 134 stitches. Knit all rows (garter stich) working back and forth. Do not join. Work until piece measures 70 inches over all. Bind off loosely.

Crochet one row sc all around afghan, working 3 sc at each corner. Be careful to keep the edge flat.

To make fringe: using a 6-inch piece of cardboard, wrap yarn loosely around cardboard. Cut one end. Strands will measure 12". Use 5 strands for each fringe section. Fold 5-strand section in half, and with crochet hook draw loop through sc. Draw ends through loop and pull tight to knot. Make a fringe every other sc around entire piece in the same manner.

Below: Thanks to James Bruce for sending me these 2018 photos of the afghan that his mother crocheted from Joan's 1972 pattern.