Screenland: January 1964

Joan Crawford: "The Hollywood I Knew"

The movies' most illustrious star looks back upon her life when she was queen bee of the fabulous film colony of yesteryear

by Dora Albert

|

|

|

FLAPPER GIRL: In 1929 Joan was the screen epitome of the gay and flip "dancing daughters" of that dizzy era. |

"If I had my life to live over again," Joan Crawford was saying, "I'd live every lovely and every sickening moment again exactly as it happened. I'd relive the three marriages that ended in divorce as well as my wonderfully happy marriage to Alfred Steele. I do not regret anything in life I ever learned from. I don't regret one moment, one incident, one experience, except Alfred's death.

"I know how lucky I was for the four years of my marriage to Alfred. Not many women have been that lucky. I remember only the beauties of our marriage and not the sadness of his departing."

We were sitting in Joan's dressing room on the Columbia lot where she was playing the starring role in "Straight-Jacket," that of a woman released on probation after spending 20 years in an institution for the violently insane. It's a strong, dramatic part, and Joan had been playing it in the mood called for -- one of near hysteria. I've known Joan for almost 20 years, and I can remember when she would have a hysterical scene. It was for a TV program, and when the filming was over, she found her way to a chair on the set and sobbed. Steele, who had come with her to the set, took her in his arms and soothed her. It was during the early days of their marriage.

|

|

|

GLAMOUR MATRON: Still a great star 35 years later, Joan is also a dynamic executive of the Pepsi-Cola company. |

Afterwards she told me how much the marriage meant to her. She had discovered, she said, what it meant to be a fulfilled woman. She had known moments of peace and happiness previously, but her marriage to Alfred Steele was the fulfillment of every dream, every hope she had ever had.

Then four years ago Steele died. The night before his death, he held her hand and said, "I want you to know, Joan, no man has ever loved a woman as much as I love you. I never knew before what marriage was."

"Neither did I," she smiled. She kissed him and turned out the light. They were both very tired, but happy.

The next morning he was gone. Joan was prostrated by grief. Yet, with the remarkable strength that has always been hers, she compelled herself to finish the arduous tour of cities on behalf of the Pepsi-Cola Company that her husband had begun. There were three more cities still to be visited, and Joan went to them all. Soon afterwards, the late Jerry Wald invited her to come back to Hollywood to make a picture. She was back in the film colony six weeks after Steele's death to go before the cameras.

|

|

|

CRAWFORD IN THE TWENTIES: Gold lame, yards and yards of it, was the royal raiment of a movie star. |

When a reporter asked her how she could work when she had known such grief, she said, "I have known wonderful success in my profession. I have turned to it again and again as an antidote to the pains that have come upon me. Work is the best alleviator of sorrow I know and once again it is standing me in good stead. So I will work -- and cry on my own time."

Elected a director of the Pepsi-Cola Company, Joan has continued her late husband's work.

"There has been comfort in carrying on Alfred's thinking," she told me. "I have traveled 850,000 miles in seven years. I never know, when I'm not working on a picture, where I will be except on a week's or month's notice. I love it. It keeps me busy. Also," Joan added smiling, "I do a good job. I entertain the bottlers and their wives, whether they come from Africa, London, Switzerland or Kansas."

"Will you get married again?" I asked.

|

|

|

CRAWFORD IN THE THIRTIES: Accordian-pleated doodads and the hat pulled down over one eye typified this era. |

She picked up a half-finished coral-colored sweater and started knitting furiously. Knitting seems to help her think more clearly.

"I haven't the vaguest idea," she said. "I hope so. It's a very lonely life I'm leading. I haven't dated since my husband died. I have many men friends, but wouldn't know how to behave on a date."

I didn't believe it, and said so. I've never known a time when Joan wasn't able to adapt herself to every changing circumstance. The girl who could go from the flapper of the 1920's to the sophisticated lady of the 30's and 40's to the fulfilled woman of the 50's and then meet widowhood with such gallantry would know how to behave on a date with any man.

|

|

|

CRAWFORD IN THE FORTIES: A more mature Joan had already discovered the frippery of earlier stardom. |

"I was married for four years," Joan said. "Alfred has been dead for four years. Those have been eight years when I haven't been interested in dates. I have many business conferences, see mostly business associates.

"I have never really been flirtatious, as many girls are on a date. My zest for living made a lot of people think I was flirtatious. I haven't lost the zest for living, not for one minute. But on the exterior, I am not as flamboyant as I used to be."

Flamboyant she isn't. When she first walked on to the set in the dark wig she wears for some of her scenes in "Straight-Jacket," dressed in the plain dark gray print the woman in the picture would naturally don, I had to look twice to make sure I was looking at Joan.

|

|

|

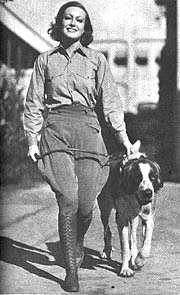

CHEESECAKE PHOTO displaying Joan's shapely legs was born in fanciful imagination of studio press agent. |

She is as beautiful as ever, with the lovely cheekbones, the ageless face, the erect posture. Still, she looked different from the Joan of ten years ago, when she was making "Torch Song." Her hair had been a flaming tawny color then. And what a great spirit of defiance she had shown! She hadn't danced professionally in 14 years. There were people who whispered that she'd never make it, that she'd look ridiculous as a dancer. In black leotards, she looked compellingly handsome. And how high she had kicked her magnificent legs!

"This is a challenge," she said then. "I could have chosen to do something easier, but I wanted the challenge. I believe God's hand is on my shoulder."

|

|

|

JOHNNY MACK BROWN: That gleam in Johnny's eyes is from early hit, "Our Dancing Daughters" (1928) |

"I don't know about your shoulder," Billy Haines, her friend of many years, had said, "but only God could get your legs up so high."

Flamboyant? Yes, Joan Crawford had a certain flamboyance about her ten years ago. Underneath she was often frightened. But as Franchot Tone, one of her ex-husbands, had taught her, "The only way to overcome fear it to pull its teeth." So whenever she was afraid of anything, she deliberately did the thing she feared. She wore a mask of self-confidence that fooled many people, but she built up that self-confidence painfully.

|

|

|

ROBERT YOUNG, FRANCHOT TONE: Alas, Joan had to choose between them in "The Bride Wore Red" (1937) |

Whenever she's afraid of anything today, she'll defy hear fears to do it. When you've had to fight all your life, you don't give up the habit of fighting. But a certain buoyancy has gone out of her, since her late husband's death. Warm and loving, when she closes the door of her Hollywood apartment at night, she can't help feeling how empty her arms are.

The two older

children she adopted, Christina and Christopher, have gone their sometimes

troubled way. When Christina was trying hard to build up her career on the stage

and in pictures she gave interviews about her "feud" with her mother. In her

book, "A Portrait of Joan," Joan wrote,

|

|

|

ROBERT MONTGOMERY: Bob made love by moonglow to a platinum blonde Joan Crawford in "Our Blushing Brides" (1930) |

"I am only filled with sorrow and compassion for my daughter because she's paying too much for whatever it is she wants. I certainly understand ambition, but you can't afford to throw away people, especially the people who love you -- and you can't afford to use them. Mother and daughter feuds make for reams of print; they also make for reams of inaccuracies. The greatest inaccuracy is the feud itself. It takes two to feud and I'm not one of them. I wish only the best for Tina."

|

|

|

SPENCER TRACY: Not the handsome profile type, Spence won the ladies with his rugged charm. The film, "Mannequin" (1937) |

Neither Christopher or Christina wanted to take advantage of all the educational opportunities Joan made available for them. Knowing how much an education might mean to their future, she was keenly disappointed. Later, Christopher admitted that his failure to get a diploma made it difficult for him to find renumerative employment.

The twins, Cindy and Cathy, 16, have the self-reliance and adaptability Joan has always wanted for her children.

|

|

|

JOHN GARFIELD: The screen's first angry young man romanced Joan in "Humoresque" (1946) |

"They're at camp now," Joan said, "because of my long working hours. When I finish the picture, they'll go East with me, and I'll put them into school there."

Putting the children into school means to Joan attending to every detail: shopping with them for their clothes, seeing that their suitcases are packed with everything they will need.

The twins are a perennial delight to her. When they were younger, she brought them up strictly.

|

|

|

CLARK GABLE: "The King" got a good grip on Joan in "Possessed" (1931) and other memorable films. |

Authorities on children say they'll turn out fine if parents are consistent in bring them up, whether they are strict or lenient.

"I want the children to be prepared for life," Joan says. She believes that if a parent is too lenient, the children will not be ready for what they'll have to face in the outside world.

When I asked Joan, "What do you want out of life now?" her knitting needles flew furiously. Then she said, "Happiness for my children and for the world -- peace. I want everything that will make their lives happy, as long as they are good citizens."

|

|

|

A RADIANT JOAN posed with another rising young star of her era, Claudette Colbert. The year was 1931. |

"And for yourself -- don't you want happiness, too?"

Again the knitting needles flew.

"I'm not that selfish. Naturally, I want happiness as it comes. But you can't force it; you can't push it. If happiness has got your name on it, fine. Otherwise you try to create it by giving it to other people."

In her marriages, Joan tried to create happiness for her husbands. She succeeded completely only with Alfred Steele.

|

|

|

ON THE SET in 1933, jodhpur-clad Joan strolled with her pet St. Bernard. |

She was 21 when she married Doug Fairbanks, Jr. She was warm, intense, almost schoolgirlish in her attitude toward love. They called each other by pet names. He called her Billie; she called him Jodo. They had their own love language...a kind of pig Latin that amused and confused friends. They called their home, "El Jodo" and later "Cielito Lindo," which meant "Little Heaven." But as Joan admitted later, it was a doll house marriage.

Within four years, they'd grown in different directions and were no longer communicating with each other.

|

|

|

TOO ILL to attend Academy Awards in 1947, Joan accepted Oscar for her "Mildred Pierce" performance in bed. |

Joan said later, "We were taking separate roads. Douglas began to develop into the sophisticate he now is. I had had my fill of dancing and parties and wanted a normal home life.

"When we'd first met, his name was better known than mine. Then, due to the unpredictable ups-and-downs of this business, I became a star. He remained a leading man. I think that 90 per cent of Hollywood's ruined marriages split on this rock."

|

|

|

EVENING FOURSOME in 1933 included, from left, Clark Gable, Norma Shearer, Joan, Doug Fairbanks, Jr. |

In 1933, they were divorced. About a year later, Joan was in love with Franchot Tone, and he with her. But it took another year for him to persuade her that they ought to get married. She had been crushed by her first marriage ending in divorce.

She was determined that nothing like that must ever happen to herself and Franchot. The marriage began on a wonderful plane of romance and understanding. Joan says she will never cease to be grateful to Franchot for the things she learned during their marriage. With Franchot encouraging her, she did something she had always feared to do: she went on the radio. Once she conquered her fears, she was superb. She and Franchot frequently appeared together on radio programs; they read Shakespeare together. Franchot, a university graduate, helped Joan to understand the deeper meanings of the bard's plays.

|

|

|

BROADCASTING in 1949, Joan was as chic and lovely as though before movie cameras. |

For Joan, there were moments of great happiness in this marriage. But Hollywood helped to destroy it. In her book, "Portrait of Joan," she tells what happened.

"There was never a doubt in my mind that Franchot's talent was greater than mine and I tried very hard to give him more scenes, to build his ego. It just didn't work. It was no wonder that he gradually broke away, tried to assert himself. He was working in a film. I wasn't. One afternoon, I dropped by his dressing room to surprise him. I did."

|

|

|

FIRST MARRIAGE, to Doug Fairbanks, Jr., ended in divorce after Joan had surpassed him as a star. |

She left that dressing room in a state of confusion and hopelessness. She had given herself completely to that marriage. From Franchot she must have expected the same.

She was not content with half a loaf or half a marriage. "I was frightened again, alone again, trying to find a way back," she wrote. "There was no way back -- I was no longer in love."

With Doug, Jr., and Franchot Tone, Joan had known ecstasy, happiness, and, finally, unhappiness. She had been deeply in love with both men. She now feels that with Philip Terry, her third husband, she didn't know the deep love she should have known before getting married. "I owe him an apology," she says. "I mistook peace of mind for love."

|

|

|

ADOPTED CHILDREN posed with Joan a few years ago. Standing, Christopher and Chistina. Seated, Cindy and Cathy. |

Finally, with Alfred Steele, she found complete fulfillment, as a woman and as a wife. She found everything she had been searching for all her life.

"If you marry again, will you marry a businessman?" I asked.

"Only a businessman," said Joan emphatically. "I do not consider the three marriages which ended in divorce failures. I consider them successes because of all I learned from them. Still, if an actress is married to an actor, it is difficult to make her marriage last. At least it has been in my case. There were many girls in Hollywood trying to prove that they could take Joan Crawford's husband away from her. This was not unique in my case. They would do this to any feminine star. No doubt there were girls trying to prove that they could take away Bette Davis' or Barbara Stanwyck's husband. It happens in the industry. You work all your life to become something and, when you have achieved it, it sometimes makes you a target.

|

|

|

SECOND MARRIAGE, to sophisticated Franchot Tone, ultimately foundered on the rock of career competition. |

"Many women in Hollywood are dangerous. A woman can trust other women, if she's careful whom she trusts. We are all -- men and women alike -- born with the same feline instincts. But those instincts are something most of us can conquer while we're still young, if we're normally well adjusted.

"I have some wonderful women friends whom I trust completely, but I know how witchy some women can be. Some of the witchiest are in Hollywood. Hollywood is a mecca for some of the most beautiful girls in America. There are far more women than men in Hollywood, and many of these women spoil the men rotten. Some, in their eagerness to attach a male, will stop at nothing. Certainly they won't stop because the man is already married or believed to be in love with another woman. To a woman like that, getting another woman's man away from her constitutes a delightful challenge.

|

|

|

THIRD MARRIAGE, to actor Philip Terry, brought Joan peace of mind which she mistook for love. |

"Many women in Hollywood openly pursue the husbands of feminine stars. Often they pursue them, not because the men themselves are so attractive, but because they want to prove a point -- that they can get a successful star's husband away from her.

"This is the Hollywood I once knew. I don't really know it any longer. For eight years I've made my home in New York. I live in the home in New York where Alfred and I knew so much happiness.

|

|

|

FOURTH MARRIAGE, to Alfred Steele, brought Joan the happiness she'd never had before. |

"Now when I come to Hollywood, I come only to work. I arise at 4:30 in the morning and work 'til 7:30 at night. I resent the fact that I rarely see the people I love most in Hollywood, but when do I have the time in Hollywood to visit friends or entertain? And to live a leisurely life in Hollywood without working nowadays would take the resources of a millionaire."

"Why do you get up at 4:30?" I asked. "Surely you don't have to wake up that early in the morning."

"Don't I?" asked Joan ironically. "I've been raised in a business where you have to get up at 4:30 mornings to study your lines and be ready to face the cameras. For an eight o'clock shooting call I'm at the studio every morning at 7:15. If I weren't, they might replace me. Someone else might be in front of those cameras."

|

|

|

On the set of "Flamingo Road" (1949), Joan checks over the results of a portrait sitting. |

"I don't think they could replace you that easily," I said.

She picked up a clock ornamented with gold trimming from her dressing table and handed it to me. On it, William Castle, the producer-director of "Straight-Jacket," had had engraved: "Thank you for giving me the greatest star in our industry to work with. Love, Bill."

"I think I'll tease Bill about it," she said. She poked her head out of the door. Castle was standing nearby.

"Bill," she said, smiling, "did you give me that clock because you wanted to reprove me for being late so often on the set?"

Her eyes twinkled.

|

|

|

In 1933, when Hollywood and glamour were synonymous Joan starred in "Dancing Lady." |

"You've never been late, Joan," he said. Even for a gag, he wasn't going to let me get the wrong impression.

"What about your career? Are you happy the way it has gone?" I asked Joan. "Has it been worthwhile?"

"It sure has," said Joan. "I wouldn't change any of it, not even 'Rain,' in which I gave a lousy performance. I wasn't ready for that part then, but I learned a great deal from playing the role. I'm always grateful for the lessons I learn."

She bears no resentment because Bette Davis was nominated for an Oscar for her performance in "Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?" while she herself wasn't.

"Months before the Awards," she said, "I predicted that Bette Davis would be nominated and would win."

"But she didn't win."

"That I'm truly sorry for."

As a reporter, I had to ask my next question. "Then why did you accept the award for Anne Bancroft?"

"Because Miss Bancroft and Miss Geraldine Page asked me to accept for them if they won and so did the Academy of Motion Picture Arts. I was free to do it. I thought it a great privilege that these two ladies and the industry asked me to accept if they won."

|

|

|

Joan's marriage to Alfred Steele was the realization of every dream she'd ever had. |

Joan doesn't live in the past and avoids bitterness or resentment. She has managed to remain friends with her ex-husbands. When Alfred Steele died, both Franchot Tone and Doug Fairbanks, Jr., got in touch with her to express their deep sympathy. Franchot flew to her side when his presence as a friend meant most to her.

"How have you managed to stay friends with your ex-husbands?" I asked.

"Obviously, we have remained friends because I meant something to them and they to me," she said. "We have never lost track of each other. I have never felt hatred or bitterness. Hatred and bitterness can cause such devastation of mind and spirit."

"Yes," I agreed, "I've seen some people who could never get over their bitterness after a divorce."

"I've seen it too," said Joan. "It shows on them."

Joan has survived many changes in Hollywood. Sometimes she laughs about her "damned durability."

"I'm not interested in taking anybody else's place," said Joan. "Sometimes it seems that you have to keep proving your right to your own place in the sun every minute. I want only the place I've earned.

"Cary Grant once said, 'After having been a star for years, I left Hollywood for a few months, thinking my stardom was secure and permanent. When I came back, the Van Johnsons and others who'd become stars in the meantime were threatening to take my place. It was like being on a bus and being pushed by new passengers to the next hand rack and the next hand rack. The new stars came up so fast.'

"That was the way it used to be in Hollywood," said Joan. "New stars used to be created all the time. But that was the old Hollywood. Now where are the new Van Johnsons, the new Barbara Stanwycks? The studios are building up scarcely any new movie talent. The biggest box-office stars today are the stars of yesterday and the day before yesterday. They're publicizing the producers' names and the names of the pictures. What big new stars have they got to sell?"

I mentioned Ann-Margret.

"What has she done?" challenged Joan.

"She was great in 'Bye Bye Birdie,' " I said.

"One good picture doesn't mean anything. If she's a star, let her prove it for ten years," challenged Joan.

"Among the newer players," continued Joan, "Diane Baker is outstanding. She has tremendous potential. Although we had very few scenes together in 'The Best of Everything' back in 1959, I was greatly impressed by Diane at that time. Now, after working with her throughout 'Straight-Jacket,' I'm firmly convinced she has impact, she projects, and she is a pro. This girl's got it."

Joan was ready for a new scene. Peggy Shannon, her hairdresser, came in and adjusted the dark wig she wears during some of her scenes. In other scenes her hair is a beautiful gray with a white streak.

Peggy brought in two of Joan's French poodles, Ma Petite, a beautiful white dog, and Masterpiece, a gray poodle. They cuddled up close to Joan. Masterpiece stood on his toes and begged for attention. Joan gently stroked his back, then Ma Petite's back.

"Where's Chiffon?" someone asked. Chiffon is Ma Petite's mother; Masterpiece Ma Petite's father.

"At the vet's," said Joan. Someone signaled her that she was needed for the next scene.

She got up from her chair and put down her knitting quietly. The two French poodles went to the door of the dressing room as though to see her off. Joan walked toward Diane Baker, who plays her daughter.

I thought of what Joan's life is like -- the twins at camp, the older children out of touch with her much of the time, the close friends in Hollywood she has so little time to be with, the endless business conferences, the TV performances in New York to spice up her days and nights.

From a warm, loving woman, how can that be enough?

"I hope," I said, "that when I see you again, you'll be engaged to be married."

A smile brightened her face.

"I hope so, too," she said.