Vanity Fair: March 2004

The Lipstick Jungle

by Laura Jacobs

The ultimate three-girls-in-the-city movie, The Best of Everything, based on Rona Jaffe's wildly popular novel, was a plush, CinemaScope, DeLuxe-color 1950s jewel, with a cast that included a trio of hot ingenues (Peyton Place's Hope Lange, supermodel Suzy Parker, and Diane Baker), plus Joan Crawford, Louis Jourdan, and a slick young Robert Evans. Talking to many of the talents behind Twentieth Century Fox's stylish cultural time capsule, LAURA JACOBS learns about the "one-man studio" who propelled it to the screen, the off-camera dramas, and why the result was far more than a potboiler-in-pearls.

The genre was a winner for the movies, right from

the start. Requirements were minimal: a big city, three pretty faces, some

wolves. Sally, Irene and Mary was the first--silent but scrappy in 1925--a tale of

three chorus girls looking for love and limelight in New York, New York (one of

them was a hungry young actress named Joan Crawford). In Our Blushing

Brides, 1930, it was three shopgirls--one of them, again, Joan Crawford.

In 1932's Three on a Match, the girls were childhood friends, all grown up and

sharing bites of the Big Apple--shiny, wormy--only this time the Joan was blonde,

as in Blondell. Throughout the 30s and into the 40s, three-girls-in-the-city had

to make room for three-boys-back-from-war. (In those days returning soldiers

were as hopeful, as vulnerable, as young women.) Two is just two: left and

right, yes and no, Goofus and Gallant. Four is fine for TV--see HBO's Sex and the

City--but one too many for film (A Letter to Four Wives was fixed by subtraction:

A Letter to Three Wives won the Oscars). Three is destiny. When blushing brides

play with matches, one girl wins, one draws, one dies.

The genre was a winner for the movies, right from

the start. Requirements were minimal: a big city, three pretty faces, some

wolves. Sally, Irene and Mary was the first--silent but scrappy in 1925--a tale of

three chorus girls looking for love and limelight in New York, New York (one of

them was a hungry young actress named Joan Crawford). In Our Blushing

Brides, 1930, it was three shopgirls--one of them, again, Joan Crawford.

In 1932's Three on a Match, the girls were childhood friends, all grown up and

sharing bites of the Big Apple--shiny, wormy--only this time the Joan was blonde,

as in Blondell. Throughout the 30s and into the 40s, three-girls-in-the-city had

to make room for three-boys-back-from-war. (In those days returning soldiers

were as hopeful, as vulnerable, as young women.) Two is just two: left and

right, yes and no, Goofus and Gallant. Four is fine for TV--see HBO's Sex and the

City--but one too many for film (A Letter to Four Wives was fixed by subtraction:

A Letter to Three Wives won the Oscars). Three is destiny. When blushing brides

play with matches, one girl wins, one draws, one dies.

Who would have thought the ultimate three-girls-in-the-city flick would premiere not in the flapper-fast 20s, the satin-slouch 30s, or the shoulder-pad 40s, but in the white-glove, bullet-bra 50s? In 1959, with considerable fanfare, Twentieth Century Fox premiered The Best of Everything, a title it took seriously. The movie was in CinemaScope, of course, as were all major Fox films after 1953, and the color was by DeLuxe. Indeed, "deluxe" was the operative word, from the orchestral score, as plush as expensive perfume (Shalimar is the boss's last name), to the running time of 121 minutes (twice that of Three on a Match), to the skyline-and-sidewalk location work that opens the movie up while holding it down to earth (un-deluxing it a little, letting it breathe). The credit sequence alone is a perk, a thrill, a tone poem to arrival, home movies meet Hart Crane. The camera flies in over a hazy Manhattan at dawn, eyes the city from the far side of the East River (a barge floats by), then glides along Park Avenue like a limo with the windows down. The streets are empty, a strange and lovely sight to any New Yorker, then slowly the rush begins, cars in tunnels and curving off ramps, girls coming up subway stairs at Rockefeller Center, girls swinging hatboxes from Bonwit's as they step out of bomb-shaped buses (Fox in the 50s loved buses).

"All that sublime photography of New York that is also so

incredibly dull," says fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi, host of the 1996 New York

screening of The Best of Everything, a revival-reunion sponsored by American

Movie Classics. "They just had a really good day and they shot it, at a slightly

good angle. And they're all going to work. You see hundreds of people going to

work. It's so inspiring."

Not least because it's carried on the voice of

young Johnny Mathis--Cognac and cream--who sings the Alfred Newman-Sammy Cahn title song as if he

were hovering between the last longing of the night and the first reverie of the

day (sample lyric: "That one little sigh-is treasure / you cannot buy-or

measure").

"I loved it," Mathis says of the Oscar-nominated song. "It was

absolutely at the beginning. I was living in a broom closet at the Wellington

Hotel"--seriously, the manager had put a bed in there--"and I walked to the

studio, which was a long way away, but I composed myself as I was walking."

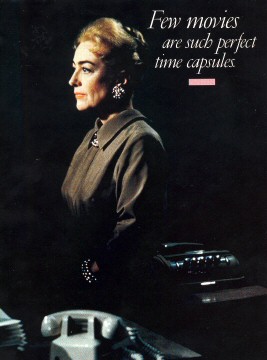

A slim melody, long-line like the girdles everyone was wearing, it has a rising inflection, lonely, yearning. This was the last song Newman wrote as Fox music director--a legendary run of 20 years--and he marked the score "Moderately (with much feeling)," not only setting the tone of the movie, the smooth, poised pace, but also capturing something of the era, the steady surface, the heart's bottled-up position within parentheses. Few movies are such pleasurably perfect time capsules, but then, perfection was a 50s ideal. There would be nothing moderate about the next big three-girl movie: in 1967, Valley of the Dolls popped open the bottle and gulped down the time capsule, along with anything else in reach.

No, The Best of Everything was a class act. "It was not just

another movie," says Julian Myers, a publicist at Fox from 1948 to 1961. "The

making of it was relatively high-charged. It had more energy and it had more

meaning." It also had a pride of Fox's most promising young stars--Hope (Peyton

Place) Lange, Stephen (Ben-Hur) Boyd, Suzy (top model in the world) Parker,

Diane (Diary of Anne Frank) Baker, Martha (future wife of producer Hal B.

Wallis) Hyer, Robert (future head of production at Paramount Pictures) Evans--and

two excellent older men: Brian (English stage actor) Aherne and Louis (Gigi)

Jourdan. And by God if the queen of the genre doesn't come up at the end of the

acting credits, but there it is, "Joan Crawford as Amanda Farrow," a name

to make film buffs weep at the rightness (and also the wrong: her first

supporting role). The most important credit, though, the muscle behind the

movie-the might, really, behind Fox in the late 50s-is the one that comes up

first, before the title: "Jerry Wald's Production of."

That apostrophe s says

it all. No producer in Hollywood history had a bigger embrace than Jerry Wald,

or possessed the stuff of movies--genres, plots, scenes, routines, even lines of

dialogue--with such brio. His mind, as director Philip Dunne writes in Take Two,

"was a magpie's nest crammed with situations, characters, and plot devices he

had gleaned from his omnivorous reading of every writer from Euripides to

Proust." And his file cabinets were famous in the business, filled with

newspaper and magazine stories--"no matter how weird, outlandish, or esoteric,"

remembers director Richard Fleischer--that might someday point to a film project,

a movie the public was growing ready for. For instance, Wald developed the WW

II movie Destination Tokyo from an article in Time.

"Wald was bigger than

life," says Julian Myers, "not really that tall but big around, and a very

colorful guy. Quick to laugh, smile, be jolly, and didn't worry too much about

who owned what. His legs moved too fast and richly to be concerned with little

things like that."

"He didn't trample on anybody," says actor and director

Mel Ferrer, a good friend of Wald's. Yet he never stopped sifting the air for

ideas. "He was the only person I ever knew who could write in his pocket,"

Ferrer continues. "He had a little pad and pencil, and if he had an idea when he

was talking to somebody, or when he was looking at a picture, his hand would go

into his pocket and he would be writing down his ideas for the plot."

"The

important thing about Jerry was his passion for movies," says writer Gavin

Lambert, who worked with Wald at Fox and wrote the screenplay for Sons and

Lovers, a literary property close to Wald's heart. "It was a medium that was his

life. No producers are like him today. You see, today, most producers have very

little training in movies."

In 1956, still only 44, Wald arrived at the Fox lot with a lifetime of training in movies--not to mention an Irving G. Thalberg Award bestowed in 1948, when he was only 36. A New York City kid born in 1911, the son of a dry-goods salesman, Wald was light on his feet. In college he fast-talked his way into a radio column at the New York Evening Graphic, jumped from there to film with a series of two-reelers featuring radio stars, and then landed at Warner Bros. in Hollywood, where he took up screenwriting (The Roaring Twenties, Torrid Zone, They Drive by Night). By 1942 he had his first producing credit--a film adaptation of the play The Man Who Came to Dinner. Some of the biggest Warner movies of the 40s were Wald's: Objective Burma!, Mildred Pierce, Humoresque, Johnny Belinda.

"Just go, go, go all the time,"

recalls Mel Ferrer, who in 1950 advised Howard Hughes to hire Wald and Norman

Krasna to run RKO, which Hughes did (Wald-Krasna Productions, 1950-52, the "Whiz

Kids," because of their initials W-K). Hughes got reports from "people" at

Warner who said, "'Jerry Wald will envision a picture and he'll be shooting in

seven days,' and it was not entirely untrue," says Ferrer.

Not only that,

adds Julian Myers, "he would promote a film before he started it."

"There was

a ceaseless flow of fanciful press releases from his office," writes Richard

Fleischer in Just Tell Me When to Cry. "He made up titles of pictures, attached

the biggest star names in town to them, and gave them to a gullible, eager press

who unhesitatingly printed everything. If a star bothered to deny it publicly,

which rarely happened, Wald would get his name mentioned all over again. Two for

one."

Despite the fact that Wald was a mensch, beloved by those he worked

with, the speed of his rise, his frightening energy, plus his panache with

publicity led some to compare him to that infamous Hollywood operator Sammy

Glick, the main character of Budd Schulberg's 1941 best-seller, What Makes Sammy

Run? It wasn't a compliment. Wald laughed it off, but friends are still quick to

his defense, chalking the charge up to jealousy.

Julian Myers: "Jerry was not

like that. Jerry Wald was a hail-fellow-well-met."

Gavin Lambert: "Oh God,

there were so many candidates for (Glick). Jerry had a lot of energy, that's

true. But he did not have Sammy Glick's attitude to movies, which was a purely

cynical one. And Sammy Glick was a sort of semi-illiterate. Well, that's not

Jerry at all."

The book's author, Budd Schulberg, himself an admiring friend:

"It was ironic we should end up working together on two projects (The Harder

They Fall, The Enemy Within), insofar as many people did point to Jerry Wald as

being the model for Sammy Glick." And was he? "One. But not the only one. He had

an enormous enthusiasm for movies, and he also wanted to do some more honest

kinds of films. So in that way I'd say he was quite different from

Sammy."

Wald went to Fox as an independent producer who would release through

the studio. And Fox needed him. The studio chief and founder, Darryl Zanuck, was

off in France making flops with French girlfriends, and the studio was in the

hands of suits who could see nothing higher than the bottom line. Wald had his

own lot, separate from the rest, tantamount to a little empire within a larger

one ("Quite unique," says Myers). In no time he was producing more movies--often

three or four simultaneously--than all of Fox's other producers combined. In 1957

this "one-man studio," as The New York Times would call him, sent out his first

mega-hit for Fox, Peyton Place. It was just the kind of "front page" producing

he liked: social issues, sensation, location shooting, and a title with

potential as a catchphrase. That same year one of Wald's files was whispering.

He could see the movie; he needed the book.

If there was one thing Wald loved

as much as movies, it was writers. Perhaps because he'd been one, he knew, as

Schulberg puts it, "he didn't have the qualities of a serious writer, and I

think he both envied and very much respected those qualities in writers. He

catered to writers in a way that a Zanuck never would." And it didn't matter if

they were famous (Wald knew William Faulkner and was close with Clifford Odets)

or just starting out.

"He treated you as an equal, never pulled rank," says

Gavin Lambert. "Working on the script was, I think, the part of moviemaking he

liked most."

Making the rounds of New York publishing houses, talking to top editors about upcoming books with movie potential, and looking for new writers who might have what he needed, Wald was waiting to see Jack Goodman, editor in chief of Simon & Schuster, when a 25-year-old Radcliffe grad came in to meet her college friend Phyllis Levy, now Goodman's secretary. Phyllis introduced Rona Jaffe to Jerry Wald. Goodman entered the room and said, "Rona's going to write a hell of a novel someday."

"And we're going to publish it,"

Phyllis added.

To which Wald said, "I'm looking for a modern Kitty Foyle. A

book about working girls in New York."

It was a reference to the 1940 film

that won Ginger Rogers an Oscar for best actress. Kitty Foyle wasn't a

three-girl movie (though Kitty does have two roommates), but it was a successful

woman's pic, the story, according to the movie's prologue, "of a white-collar

girl" who braves "that 5:30 feeling" while waiting for Mr. Right. And it had a

hospital scene actresses kill for, super sudsy, a soliloquy of sorrow for

Rogers--face framed in white sheets--who has just lost her out-of-wedlock

baby.

Jaffe read the book by Christopher Morley and thought it was dumb. "He

kept making an issue about Kitty getting her period. I thought, He doesn't know

anything about women. I know about women. I'm in an office." Still, she let it

drop. But when Jaffe and Levy went to Hollywood on vacation, they called up Wald

for lunch, and Jaffe, casting about for conversation, said, "'I'm going to write

that working-girl book.'

"So he said he was going to produce it, and he sent

me over this ton of scrapbooks that he'd collected on girls, with all this stuff

like Tampax ads--it was really crazy. And then coming back on the train from

California, coming into New York I got this vision of the beginning of the book,

which is all the girls walking to work." The train ride produced a title too, a

phrase remembered from The New York Times, a help-wanted ad that began: You

Deserve the Best of Everything.

Jaffe wrote under the daily supervision of

S&S's rising star and eventual editor in chief, Robert Gottlieb (Goodman had

died suddenly of a heart attack). Charging her to "look back in horror and

write," he called Jaffe every morning to hear what she'd be working on, then

called back at five to hear what she'd written. Meanwhile, Wald was churning out

press releases, announcing stars who were signed to The Best of Everything, even

though none were, names like Paul Newman, Lee Remick, Orson Welles (basically,

the cast of Wald's terrific The Long Hot Summer). When Jaffe wrote to say she

was pleased they'd cast Newman, Wald answered, "Paul Newman will never be in The

Best of Everything. He's under contract to Warner's. And Jack Warner wouldn't

even give you his earwax."

"Jerry was encouraging in a kind of scary way,"

says Jaffe, "because there was stuff in the paper every day about how he was

doing this movie of a book I hadn't written, which he hadn't seen."

The

437-page novel was finished in five months and five days, and Fox bought it for

$100,000 before it was even edited. As Michael Korda, another Young Turk S&S

editor at that time, has written, The Best of Everything was "the very prototype

of the hot 'women's novel.'" Wald's synergistic purchase gave the book landmark

status in publishing: it meant the studio would help with the marketing. And it

put a big spotlight on a young writer. The first-edition book jacket wears an

expensive photograph by Philippe Halsman--a chill gray Rockefeller Center on a

chill gray day--and half shadowed in the foreground (not stuck in black and white

on the back) is the author herself in red kid gloves, a pulp accent on the hands

that typed this "unabashed, fact-facing" novel. Despite condescending reviews

from sniffy--dare one say sexist?--male critics (Time: "It would have been too

much to ask that Author Jaffe produce a second Sister Carrie ... "), The Best of

Everything made the New York Times best-seller list by September 21, 1958, two

weeks after publication.

"People were just waiting," says Jaffe. "They ran

ads for a long time before it came out, things like 'The girl who's in love with

the married man is in The Best of Everything.' And the second it came out,

everybody was reading it."

Though the book is full of white collars and 5:30 feelings, Fox didn't acquire Kitty Foyle exactly--or, rather, it got five Kitty Foyles. The flap copy says, "These are the girls who didn't become wives at twenty... They are today's girls who gravitate to New York to play at careers while they wait for what they really want: a husband and a home." And Jaffe would know. She interviewed 50 women about their lives to make sure her own experiences weren't an anomaly. "This is a sociological novel," she says. Sequences like April Morrison's abortion, when she's driven in a black Cadillac to a doctor in New Jersey--more shocking, sad, and true than Mary McCarthy's famous "pessary" scene in 1963's The Group--are based on the confessions of friends. "These things happened to people," says Jaffe. "They didn't even give you anesthetic, because they thought they might be raided and they wanted you to be up, to run away." Sensation, social issues, and a winning title. While the book was enjoying its five months on the best-seller list, the movie was well under way.

Jaffe decided not to do the

screenplay, because she didn't know how. She wasn't thrilled, though, when the

writer they hired, first-timer Mann Rubin (his background was in television),

said, according to Jaffe, "'Oh, I know these girls. They're the ones that

wouldn't go out with me when I lived in New York. I'm going to show them.' I

thought, Oh my God, he hates my girls."

"I never said that," insists Rubin,

who went on to an award-winning career and is proud of his contribution to the

script. "I got the assignment from Jerry Wald, who asked me if I'd ever dated

young career women in New York. And I said, 'Every chance I got.'"

Dates or

no dates, it wasn't a match. Having written three drafts, Rubin--young, feisty,

and not the least bit interested in teaming on the screenplay--was replaced by

Edith Sommer, a reliable hand.

"Edith was a very good solid writer," says

Gavin Lambert. "And The Best of Everything was the kind of thing she was best

at, what Variety used to call 'a good programmer,' which meant a superior

commercial movie."

And who better to direct a superior commercial movie than

Hollywood pro, Zanuck favorite, and crown prince of the three-girl movie Jean

Negulesco?

He was a Wald favorite, too. Negulesco had come up through Warner

Bros. in the 40s, directing movies in which his noir flair in black and

white--developed as a painter in Paris in the 20s and as a Hollywood sketch

artist for title designs in the 30s--blossomed darkly, orchids in the dusk. In

fact, some cite Negulesco's first success, The Mask of Dimitrios (1944), as the

first film noir. It was at Warner that Negulesco forged a friendship with Wald,

doing superb work directing two Wald greats, Humoresque and Johnny Belinda. Jack

Warner fired Negulesco for the latter, mid-picture, hating the pictorial

approach: too much silence, too many mood shots. Wald told Warner, "If Negulesco

leaves the picture I leave the studio." In 1948, Johnny Belinda was nominated

for 12 Academy Awards. Negulesco, however, was done with Jack Warner. He'd been

summoned by Zanuck, and that same year he made an odd, compelling, noir-ish hit

for Fox, Road House, starring Ida Lupino. Still, his noir days were

numbered.

Of Romanian birth, Negulesco was charming, worldly, a womanizer

supreme--his bungalow on the Fox lot, where he invited ladies for lunch, was

known as his "bangalow," where he sometimes had them for lunch. "Poor Dusty,"

Wald's widow, Connie, says of Negulesco's beautiful wife, "(she) had to put up

with a lot." The couple quickly became members of Zanuck's croquet-playing inner

circle (Zanuck on Negulesco: "Jesus, he was cunning... He was always complaining

that someone had committed a foul on his ball"), and Fox was good to Negulesco

materially. But, artistically, he would soon be up against huge odds--how to be

stylish within the vast, static, cruise-ship bloat of CinemaScope in DeLuxe

color, Hollywood's panoramic answer to the audience-stealing TV screen.

Negulesco's last regular-format, black-and-white film at Fox--Titanic--feels like

an omen. Film critic Andrew Sarris, in his book The American Cinema, puts it

bluntly: "Jean Negulesco's career can be divided into two periods labeled B.C.

and A.C., or Before CinemaScope and After CinemaScope."

Sarris sees it as a

qualitative difference, but the divide is also gender-oriented--a creative,

masculine dynamic in black and white versus the slower, chattier,

color-me-spring woman's picture. Negulesco happened to be very good with

women.

"He adored women, was terrific with them," says Leslie Astaire, whose

father, Monty Berman, of the famous costume company Berman's, was a good friend

of Negulesco's. "He made you feel that he was concentrating on you."

And there were a lot of women at Fox on whom to concentrate (Zanuck concentrated on a new one daily, from 4 to 4:30). When CinemaScope came in and the three-girl movie seemed a good way to fill out that wide screen, Negulesco was Zanuck's pick to direct. And the movies made money. Where Johnny Belinda was Negulesco's greatest critical success, it was 1953's How to Marry a Millionaire, his first movie in CinemaScope and his first try at three-girls-in-the-city, that drew the biggest box office of his career. In 1954 he directed two more three-girl hits: Three Coins in the Fountain, much of it shot in Rome, and Woman's World, back in New York. All three films had long location openings under the credits, like travelogues or tourist snapshots--the most interesting camerawork on each reel (yet none comparable to The Best of Everything's opening). In scenes done on Fox sets, it's pretty much actresses trying to look natural in football-field living rooms with prop-shop furniture oddly scaled. There were some delicious performances--Monroe in Millionaire, hilarious in Coke-bottle lenses; Arlene Dahl in Woman's World, a whipped-cream diva--but Negulesco doesn't have much to do in these mindless rooms. As for the three-girl genre, where once it had been a classic cautionary tale, in these films it was a bit sitcom, the girls all good, if silly to various degrees, and the ending happy, if padded out like the decade's worst Dior cocktail dresses. The tale had lost its teeth.

The Best of Everything was

different. To begin with, the book had five girls, and bad things happened to

them. There's virginal Caroline Bender, who throws herself into work after her

fiance marries another; Gregg Adams, the aspiring actress who loves, then

stalks, a controlling theater director; April Morrison, a daisy plucked and

tossed; Barbara Lemont, a divorcee in love with a married man; and plain Mary

Agnes, busy planning her wedding. Furthermore, the movie had a conscience--Rona

Jaffe--who was involved every step of the way. The most important thing, she told

Negulesco again and again, "is that it is real, real, real." She was "a true

believer in details," Negulesco wrote in his autobiography, Things I Did ... and

Things I Think I Did--"sets, clothes for the girls, their way of

living."

Negulesco heeded Jaffe, as did cinematographer William C. Mellor and

the team of three art and two set directors. The Best of Everything rewards the

eye at every turn, beginning with the very first scene, when Hope Lange

(Caroline) is about to enter Fabian Publishing--i.e., the Seagram Building in all

its spanking, gleaming, one-year-old grandeur. As she pauses in front of the

building, Lange's little crop jacket flies open to reveal a polka-dot lining--so

right, so Traina-Norell. In an interview before her death last December, Lange

said it wasn't planned, no wind machine--it just happened. And that's how the

camera works, never pointing anything out, just gliding like that limousine and

taking in details. The Fabian offices--a set modeled on Pocket Books Inc., the

paperback publishers of The Best of Everything--are a Mondrian you could live in,

"Broadway Boogie Woogie" in coral, mustard, French blue. The Fabian desk lamps,

they're like Balenciaga hats. The cramped apartments of editor Amanda Farrow

(her chandelier hangs at a mesmerizing shoulder height) and theater director

David Wilder Savage (books, books, and African art) are two versions of Michael

Greer midcentury chic. Look at the way Lange leans against a wall--that Vogue

slouch taken straight from 30s movies--and the way Suzy Parker sleeps on the bus

ride to the company picnic (Fox in the 50s loved company picnics), as if Avedon

were only rows away, focusing his Rollei. Notice the pearls, one strand, two,

three, as if the number designated rank within the company. And that subtle

code--who wears a hat and who doesn't.

Other details, however, did change.

Jaffe remembers what she calls the Great Virgin Conference, something between

Playboy and playing house, where the top men, in all sincerity, "sat around

deciding which girl should be a virgin and which shouldn't. They didn't care

what was in the book. They decided this one is and this one isn't. They decided

that Caroline had to have had an affair in college. And who should be pretty,

who should be blonde, who should be brunette."

There was, as well, a sixth

character to consider, Amanda Farrow, the girls' superior at Fabian, an icy

older woman mostly absent, off to matinees (and we don't mean The Theatah) with

a married company V.P. Wald had an idea that the role should go to Joan

Crawford. In the 40s he had rescued her career by championing her for the

part of Mildred Pierce (if Crawford owed that Oscar to anyone, she owed it to

Jerry Wald). He'd let her do Humoresque, even though he thought the part too

small for her. And when her fourth husband, Alfred Steele, chairman of

Pepsi-Cola, died suddenly of a heart attack, Wald called Crawford a week later.

"I thought that coming out to Hollywood and working would take her mind off her

troubles and be good therapy for her," he told Life magazine.

"But it's a

nothing part," Negulesco had argued. "She'll never do it."

Wald: "Not after I

put in the scene that every actress will sell her soul to play." He then

described the exact same getting-drunk-in-a-smoky-bar scene that Crawford had

done in Humoresque. Negulesco pointed out the similarity, adding, "It doesn't

belong here."

Wald: "It's a good scene, Johnny. And it may get us Crawford." Which it did. (When The Best of Everything came out, the scene was gone.)

And then there was the Hays

Office. Just as 1957's Peyton Place never quite uses the word "rape" (Anatomy of

a Murder, two years later, was thought daring for tossing the word around), The

Best of Everything could not use the word "abortion"--in the movie it's "an

operation"--and heaven knows the censors couldn't let April-the-innocent

(adorable Diane Baker, straight from filming Journey to the Center of the Earth,

with Pat Boone) actually have one. Instead, in a scene that required stopping

all traffic in Central Park for a day, cad boyfriend Dexter Key tells April he's

driving her to a doctor--forget marriage--and she jumps out of the moving car,

conveniently losing the baby. When she wakes up between white sheets, Caroline

bending over her, it's none other than that Kitty Foyle hospital scene, but with

a 50s twist: the definitive, and probably the most dated, line of the movie

(which Jaffe didn't write and thinks "stupid"). Diane Baker delivers the line

with much feeling: "I'm so ashamed"--face turns away--"now I'm just somebody who's

had an affair."

"I'm so ashamed," quotes Isaac Mizrahi. "Exactly. I think

that's why the movie resonates with homosexual men. The whole plight of women in

that time period, it's like homosexuals are living that today. We're like 50

years behind the times. It's true, I tell you, it's true."

April is rewarded

for her suffering with a handsome young doctor--played by Ted Otis, a clever

extra who was Johnny-on-the-spot when it came time to fill this bit part.

Hmm--Kitty Foyle ended up with a doctor, too.

"The handsome doctor," Rona

Jaffe harrumphs. "I thought that was more immoral than in the book. Because

that's not the way life works."

Casting was done with the usual Wald

esprit--contract players, plus catch-as-catch-can. Hope Lange, of the deep-blue

angel eyes, and Diane Baker, both Fox ingenues, were coming off critical

successes: Lange in Peyton Place, where she played incest victim Selena Cross,

and Baker in Diary of Anne Frank, where she played Anne's older sister. And for

the glam-tragic role of Gregg Adams, why not the most glamorous face in

America?

"I wanted Suzy Parker," Jaffe recalls. "I met her on the beach in

St. Thomas, when I took myself on vacation. I went up to her and said that I had

written a book and I wanted her to be in it. And then I guess she read it and

sent Jerry Wald a little note saying she wanted to be Gregg."

Parker, 26, was

under contract at Fox, having been recommended for her first real film role (in

Kiss Them for Me) by Audrey Hepburn. Wald thought she could be a big star, a new

Grace Kelly, and in 1959, Parker certainly had presence. Her breeziness,

knowingness--those pussycat cheekbones, that tumbling red hair--the way she tips

up her chin, lowers her sunglasses, all lend the movie a kind of haunting

sophistication, a sensation of the real thing. Nevertheless, Gregg Adams wasn't

an easy role. Dumped by theater director David Wilder Savage, Gregg becomes

obsessed, unhinged, picks through his garbage, spies from his fire escape. As

Parker's Gregg grows needier, the camera tilts and the movie darkens. "It sort

of set a tone for my life," confesses Isaac Mizrahi. "The whole loneliness of

all the different romances gone wrong. Suzy Parker and Louis Jourdan--oh, that's

such a sad, horrible plot." (During filming, Parker was early in her first

pregnancy--a happy thing, daughter Georgia--which may have added to her

bloom.)

Though Hope Lange was the unspoken star of the movie, it became quite clear that Joan Crawford, now 55, was the star of the set. She arrived at the studio in a limousine. She swept in, dressed to the nines, with an entourage that included a hairdresser, makeup artist, wardrobe mistress, secretary, chauffeur, and stand-in (all the other girls shared Fox staffers), and nobody would say good morning until she said it first. Crawford played the ice-queen editor in the movie, and, fittingly, when she was on the set it was kept cold, very cold, six degrees below normal temperature, and not just because she had coolers full of Pepsi for the cast and crew, and a special cooler of 140-proof vodka for herself.

"That was my first awareness,"

remembers Diane Baker, "that an artist had that kind of (power). She had to have

the set freezing. People caught cold. We all tried to figure it out. Someone

came up with the solution; it had to be because of her makeup."

And yet,

despite the cold, Crawford was in meltdown. She was mourning the loss of Steele,

the end of her happiest marriage, and was desperate about money. She told gossip

columnist Louella Parsons that she accepted the small role (for which Wald

reportedly paid her $65,000) because Steele's death had left her "flat broke."

This in turn infuriated the executives at Pepsi-Cola, who felt smeared, so

Crawford had to recant the comment, saying there was a "misinterpretation"

(which teed off Parsons, who never forgave her). Crawford's drinking was an open

secret on the set, and though she was never visibly drunk, Jaffe once saw Madame

Perfectionist in mismatched sandals, one turquoise, one beige. Crawford would

later say to writer Roy Newquist, "After Alfred died and I was really alone, the

vodka controlled me. It dulled the morning, the afternoon, and the night." Did

it? On-camera, Crawford was a consummate professional. But off-camera, to the

young women around her, she seemed out of control.

"She was pretty much a

vulnerable, tear-ridden person, trying to hold it together," says Diane Baker.

"She was crying one day, before a take. She was scared to death. I just gave her

a positive sign, like 'Yes, you're going to be fine.' It sort of solidified a

... kindness." In turn, Crawford adopted Baker as a protegee, which was fine

until they met again on the set of Strait-Jacket, and a recovered Crawford--"She

was the boss again"--cut Baker and her scenes down to size.

Suzy Parker,

disturbed that some of the younger actresses were treating Crawford like an old

has-been, was quick to help her. Parker befriended the aging star, acting, her

husband Bradford Dillman says, "as kind of a shield to Joan." What she couldn't

know was that she herself, her status as the top model in America, intimidated

Crawford. Eve Arnold, who photographed Crawford on the set for Life magazine,

says, "Joan was in competition with Suzy--she was very much in the news. (But)

Joan was smart enough to leave that alone."

The only outright tension was

between Hope Lange and Crawford, between the star with first billing and the

name that came last. Amanda Farrow, after all, was Crawford's first supporting

role--a comedown.

"I was fortunate because there was tension," said Lange.

"Our scenes were built-in with tension. It had to have been tough to have all of

these young upstarts, and there she was in a non-starring role."

Asked just

how in or out of control Crawford was on The Best of Everything, Eve Arnold

says, "Joan Crawford was an actress. It was hard to tell what state of

mind she was in. Indeed, she played the part of the widowed wife--little black

hat, dressed all in black, sitting at the Pepsi-Cola boardroom table for Life

magazine."

No doubt Crawford was feeling vulnerable, but clearly she knew how

to use that vulnerability. And when it came to delivering her lines, baiting

repartee punched up by Gavin Lambert, her darts over the desk take the skin off

your nose. Years later, in conversation with Newquist, more baiting: "The

youngsters did all right," Crawford said, "but for some reason or other I'm

proud to say I sort of walked off with the film. Perhaps it was the part--I had

all the balls--but I think it was a matter of experience, knowing how to make the

most of every scene I had."

Still later, with biographer Lawrence J. Quirk,

the truth: "All those young bitches," she called them.

The men were easier. Both Louis Jourdan and Brian Aherne did the movie as a favor to their good friend Negulesco. (Jourdan was also in Zanuck's croquet circle, and the best player of all.) Aherne, who'd cut his teeth touring with the playwright Dion Boucicault, and who'd conquered Broadway with actress Katharine Cornell, plays the lascivious Mr. Shalimar with a twinkle and a sigh, twirling his lines like the ends of a mustache. (Note to film queens: Marlene Dietrich reportedly rated Aherne the best lover she'd ever had.) As David Wilder Savage, Jourdan plays with a light touch and a cold eye. Both men brought their skills to bear on the script (Wald was known for endless tinkering), with Aherne writing a scene of cozy camaraderie between Shalimar and Farrow, and Louis Jourdan adding the Ping-Pong ball speech--"You're reaching for your hat with every word."

Dashing Stephen Boyd was a coup

for the movie, considered a hot property because of his big role in the upcoming

spectacle Ben-Hur. There, he was the sadistic Messala, stealing scenes from

Charlton Heston; here, he's editor Mike Rice, a lush and a gent, the man who

waits for Caroline, who in turn rescues him. Boyd was well liked, a nice guy

with a quiet side, an actor's actor, as respected by his colleagues as the other

young male lead, gleaming Robert Evans, a part-time actor, part-time businessman

(Evan Picone, women's sportswear), was not.

"I suppose the title of my

current picture, The Best of Everything, sounds like the story of my life,"

Evans told The Saturday Evening Post. "The truth is that I've been bedeviled by

frustrations since I started balancing two careers... In Hollywood most actors

give me the big-freeze treatment when I walk onto a set. To them I'm a pants

manufacturer out for kicks."

Norma Shearer groomed Evans to play her husband

Irving Thalberg in Man of a Thousand Faces. Zanuck groomed Evans to play a

Valentino of a matador in The Sun Also Rises. Now Wald was grooming Evans as the

new Tyrone Power. "Groomed" was the word. Lange, Baker, and Jaffe all describe

young Evans the same way--"slick"--beginning with the Brylcreem. Negulesco, who

took an instant dislike to Evans, got furious every time Evans went into the

bathroom: "He's in there combing his hair," Negulesco would fume. In fact, he

didn't even want to audition Evans. "Over my dead body," he roared when Jaffe

suggested it. She, however, saw the likeness between Robert Evans and Dexter

Key--"I thought it was a compliment," Evans says, "until I read the book"--and as

Evans was dying for the part, she got him a reading. He wasn't bad, and watching

the movie you can't say he's not convincing as a cad. But if he was hoping for

more respect as an actor, The Best of Everything didn't bring it. Evans's fourth

film was his last.

There tended to be a merry atmosphere on Wald sets. He was

a great family man, that rare Hollywood mover who was true to his wife. His

ebullience, his kindness (he was ruthless where he needed to be, when it came to

the finances of moviemaking), made people want to be around him. Diane Baker: "I

used to go back to his office whenever I wasn't on the set or working. I'd pop

over and, usually, guess who was there. Bob Evans. He spent a lot of time trying

to learn producing from Jerry Wald."

"That's very true," says Evans. "I knew

one thing. I wanted to move on. I wanted to be him and not me." Evans did move

on, producing such critical and popular successes as Rosemary's Baby, Love

Story, The Godfather, Parts One and Two, and Chinatown--a hit parade described in

his memoir (and the award-winning film), The Kid Stays in the

Picture.

Negulesco was as easygoing as Wald. "He was a kick to work with,"

said Hope Lange. "He was a big flirt. He used to call me Miss Slivovitz. At the

same time, he was disciplined. He knew what he wanted."

"He exactly knew what

he wanted us to do," seconds Baker. "And we just did it. And for that reason I

think it was great fun to be on that picture. And you can tell it."

The

scenes with Lange, Parker, and Baker--the three roommates--"those scenes with the

three of us were fun scenes to play," says Baker. Suzy Parker, "she was very

funny and we all laughed. Hope was great. Working with all of the girls, and in

that atmosphere, it took a lot of the strain off of you."

Negulesco even

softened on Robert Evans, ending up good friends with him. "He gave me a great

line," Evans recalls. Quote: "When I was your age, Bob, I used to love to make

love. As I got older I used to like to watch people make love. Today I like to

watch the people who watch the people make love."

Again, the only pea under the pillow was Crawford. And as far as Negulesco was concerned, it was been-there-done-that. Back in 1946, on the set of Humoresque, Crawford had cried when she felt she wasn't getting enough help from Negulesco, input into her character Helen Wright. Negulesco solved the problem by drawing a flattering portrait of Crawford as Wright (plus another form of input: they reputedly had an affair). In 1959, Negulesco was no longer swayed by those tears. In fact, he caused a flood of them when, in front of the entire cast, he criticized Crawford's "lousy taste" in art, those kitschy big-eyed Margaret Keanes she collected (of course, he collected Bernard Buffet, iffy in another way). And when Wald asked Crawford to introduce a young actress in a test scene, another contretemps. Crawford insisted on playing the scene holding a bottle of Pepsi (her condition for doing the scene for free). Negulesco objected, to which she said, "No Pepsi-Cola bottle, and Joan Crawford goes home." He replied, "No, Joan. Pepsi-Cola stays, but Negulesco goes home." Again, waterworks. "Crash, tragedy, hysteria," Negulesco reports in his autobiography. "Joan put on menthol tears."

Filming took two months, and when

it was done, Wald had a movie considerably longer than the optimal two hours.

Test audiences weren't responding to the Martha Hyer-Donald Harron pairing--the

most heartrending romance in Jaffe's book, and the most popular. Both were

strong actors. For her performance in Some Came Running, Hyer had been nominated

for an Oscar, and Harron had done serious work on Broadway. The problem was his

age; he just didn't meet audience expectations of the older and wiser Sidney

Carter. Bit by bit Hyer and Harron were cut from the movie until theirs was

merely a mirage of a romance, a glance here, a meeting there, then gone. Gossipy

Mary Agnes, played by nightclub comedienne Sue Carson, was never more than a

secondary character, salt of the Bronx. No, as The Best of Everything moved

through final edit, that inviolate law of filmdom imposed itself: No More Than

Three. Lange, Baker, Parker. By the time it was finished, The Best of Everything

was a throwback: Our Blushing Brides in Mollie Parnis and pearls.

Press for

the movie was very Jerry, an aggressive, creative campaign--the bullet-bra

approach. While The Best of Everything was much more sophisticated than Peyton

Place, it was aimed at the same audience (and with the same cinematographer, the

movies had a similar look). "There weren't many openly sexy movies at that time,

and Peyton Place was supposed to be one," says Julian Myers. "It was sort of a

naughty picture, so we tried to ride on that notoriety."

Ride they did. In

some ads, the o in the title's "of" was a wedding band, and the text read, "The

story of the girls who claw and scratch their way to the top ... only to realize

too late--there's no wedding ring on their finger!" Snapshots of each couple,

each containing a line of dialogue (example: "I had the finest husband ... too

bad he wasn't mine"), would wheel in a circle, or run vertically, like those

photo-booth strips. The Halsman cover of Jaffe's book was often reproduced

within the ad--a seal of approval--even as Jaffe's sympathetic portrait of single

women was being hyped as "The Female Jungle Exposed." A steady drumbeat of

coverage led up to the film's release, splashy photo spreads in Life magazine on

Suzy Parker ("A Gay Soaking for Suzy"), Martha Hyer ("Nothing but the Best"),

and Joan Crawford ("The Durable Charms of Joan the Queen"). And in big

cities around the country secretaries vied for the title Miss Best of Everything

Secretary. The winner got a line in the movie, playing an assistant who chases

after Caroline. (She calls, "Oh, Caroline," and Hope Lange answers, "Not now,

later, Dinah.")

This promotional strategy--potboiler in pearls!--belies the

gentle, contemplative quality that paces the movie, and those Negulesco grace

notes, none lovelier than the movie's ending, when Hope Lange leaves the office

at five on a Friday, coming out to a blue sky and cool sun, and finds Stephen

Boyd waiting. Looking up at him, never speaking, she removes her hat and smooths

her hair--a two-part gesture that would be lost to the culture by the mid-60s.

Then they turn, never touching, and walk south on Park together. It's all, it's

nothing, it's perfect.

The Best of Everything had a lavish premiere at New

York's Paramount Theatre, a grand old movie house on Broadway. When the reviews

began appearing on October 9, 1959, they were mostly positive, though male

critics continued to condescend. Time: "The Hollywood version of the big city is

a sort of cautiously diluted Scotch-and-Sodom."

"Women's picture!" says

Jaffe. "They said to me, 'Do you mind that you're known for writing women's

books?' I said, 'Why? Because women write about stupid things like

relationships, and men write about really important things like killing?' You

know, that was their attitude."

"Bound to, I think," says Gavin Lambert.

"Because it was that kind of movie. It was deliberately aimed to be a popular

hit. It was very successful."

"It was one of the big pictures of the year,"

says Robert Evans. "And I was the heel of the year."

"A huge hit," says Jaffe. "It was a date movie. I have friends who were married, and their first date was The Best of Everything."

As for romance on the set, if the

bangalow was busy, it wasn't with any of the stars. Hope Lange and Stephen Boyd

lunched daily together in the commissary, and because of these lunches several

columnists began to imply that the two were in love. Lange, then married to

actor Don Murray, "became so upset over these rumors," wrote Photoplay, "that

she nearly suffered a nervous breakdown." But of Boyd, who died in 1977, Lange

had only fond memories (and she still wondered what aftershave lotion he wore):

"During the film we had a great camaraderie. He had that wonderful Irish charm,

and wonderful humor. And anyone who has humor I'm a sucker for."

And the

"heel of the year," when it comes to all those pretty Fabian secretaries, he's a

gentleman. "I wanted every one of them," says Robert Evans. "And I'm not going

to tell you who I got."

But Jaffe's talking. "The only affair on the set I

knew of was mine."

Who?

"Donald Harron. Just the week he was in New York.

He and Martha Hyer were doing a scene in the sculpture garden at MoMA"--it didn't

make it into the movie--"and when I saw him I just thought he was so cute. He

said, 'You must hate me because I'm so wrong for the part.' And he was--he was

much too young. I said I didn't hate him, and then we talked, and then he said,

'Do you want to fall in love with me?' And I said, 'Yes.'

"Isn't that heaven? So 1959. It was so out of The Best of Everything."

Photo Credits from article

GRAPHIC: LADIES'

DOOM Model Suzy Parker (who plays ill-fated secretary Gregg Adams) reports to

Joan Crawford (as bitter book editor Amanda Farrow) in a scene from the 1959

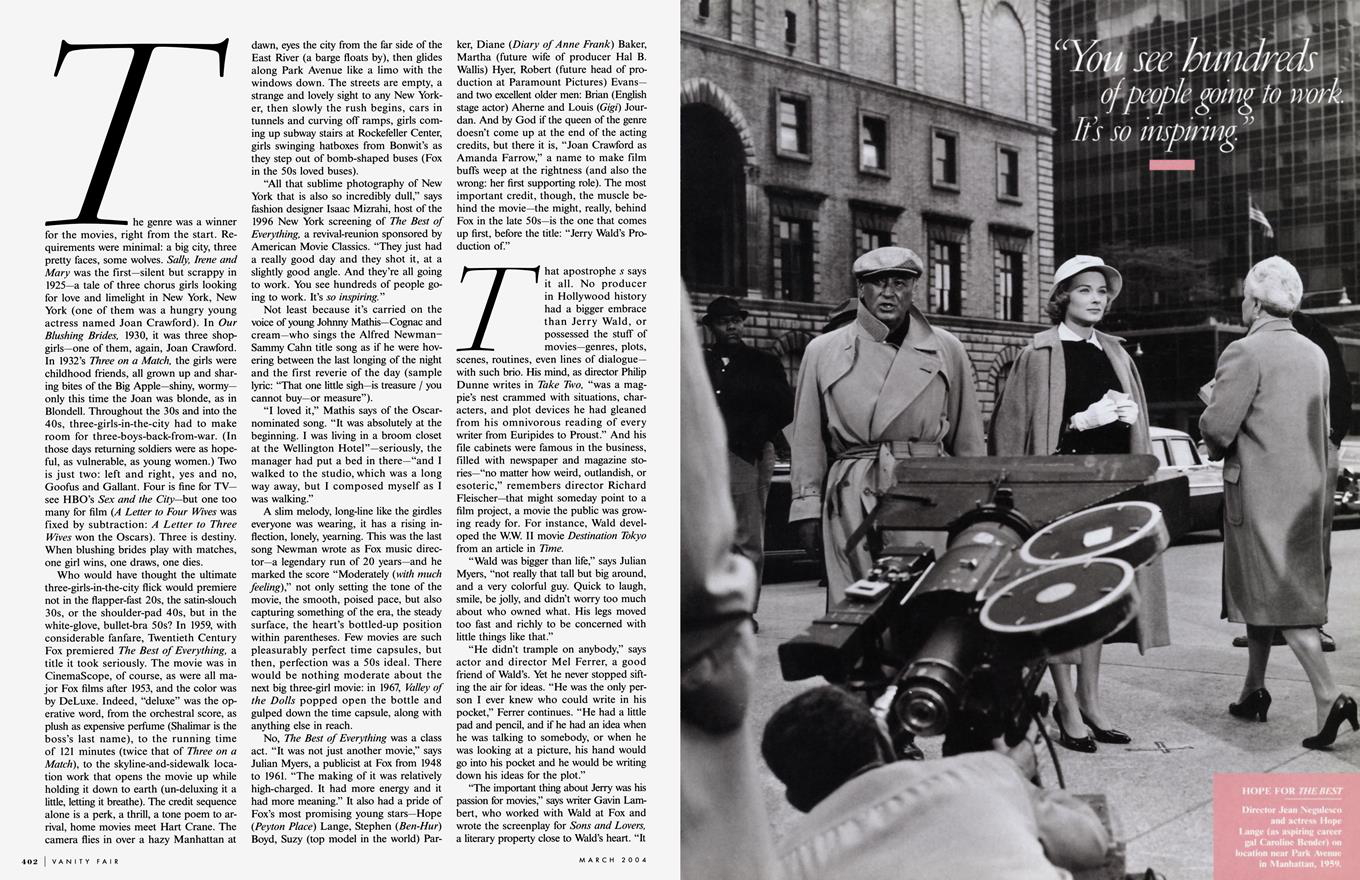

hit The Best of Everything. ; HOPE FOR THE BEST Director Jean Negulesco and

actress Hope Lange (as aspiring career gal Caroline Bender) on location near

Park Avenue in Manhattan, 1959. ; HATS OFF (1) The Best of Everything author

Rona Jaffe and director Jean Negulesco on location in front of the Seagram

Building, on Park Avenue, during production in 1959. (2) Hope Lange and Suzy

Parker in the company-picnic scene. (3) Parker and Louis Jourdan (David Wilder

Savage) during a break. (4) Diane Baker (April) and Lange on the job at Fabian

Publishing. (5) Lange and Stephen Boyd (Mike Rice) having one too many at his

apartment. (6) Baker and Robert Evans (Dexter) meet cute. ; TAKING FLIRTATION

With more than dictation on his mind, Brian Aherne (Fabian Publishing boss Mr.

Shalimar) has summoned Diane Baker (April) from the secretarial pool. ;

CINEMASCOPING (1) Robert Evans and Diane Baker in a still from The Best of

Everything's dramatic car scene. (2) An on-set portrait of Joan Crawford

by Eve Arnold. (3) Stephen Boyd and Hope Lange on a New York street after Mary

Agnes's wedding. (4) Brian Aherne welcomes Lange to her exciting new job at

Fabian Publishing. (5) Producer Jerry Wald, director Jean Negulesco, and Sammy

Cahn surround composer Alfred Newman at the piano. (6) Lange, Suzy Parker, and

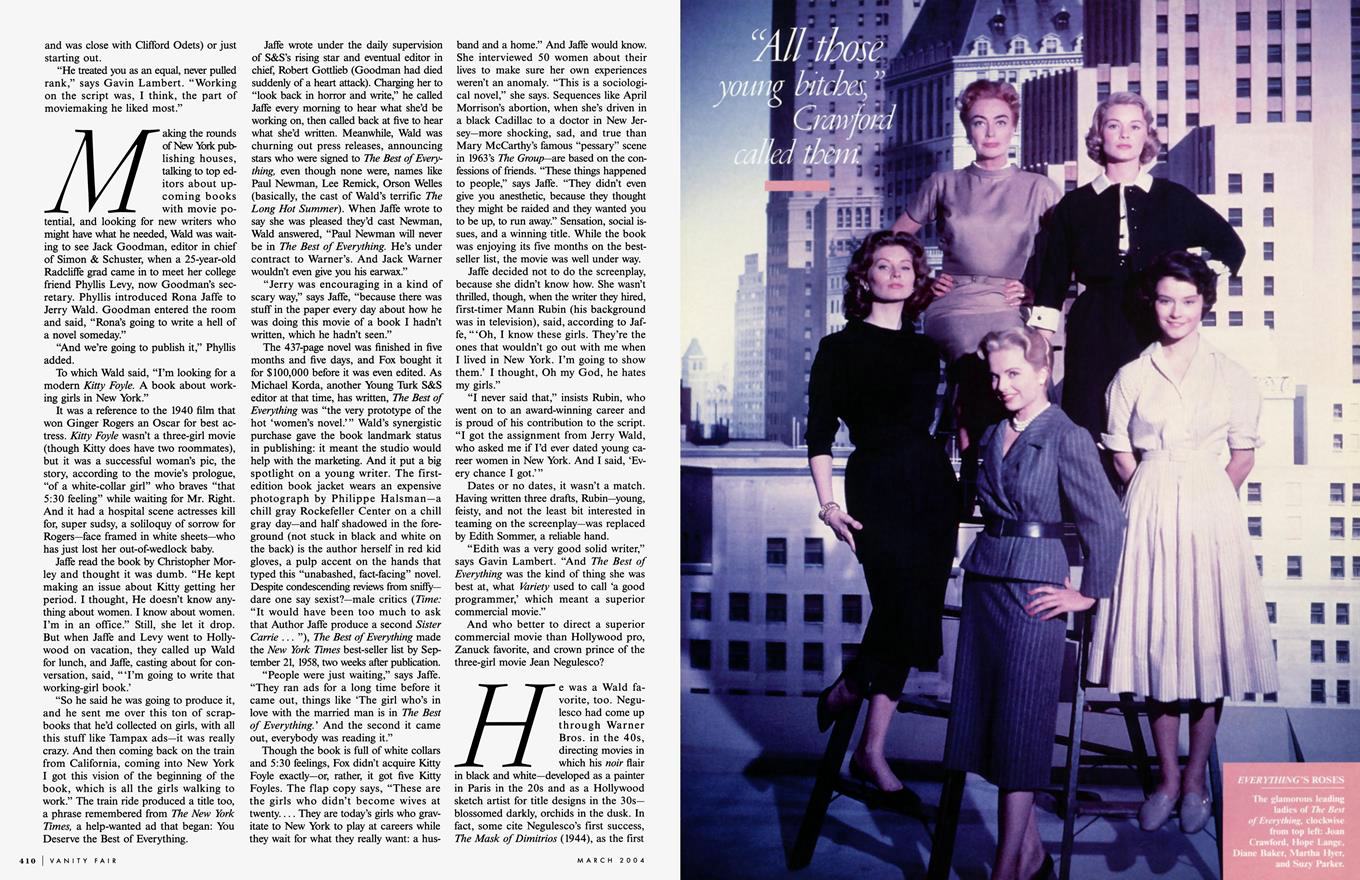

Baker have cocktails at their bachelorette pad. ; EVERYTHING'S ROSES The

glamorous leading ladies of The Best of Everything, clockwise from top left:

Joan Crawford, Hope Lange, Diane Baker, Martha Hyer, and Suzy Parker. ;

EVERYTHING GOES Joan Crawford, Stephen Boyd, an unidentified man, and

Hope Lange on the set of the 1959 film The Best of Everything. ; Pages 400-401:

From the Ronald Grant Archive. Page 403: From Photofest. Pages 404-5: Courtesy

of Rona Jaffe (1), from Movie Still Archives (4), from Photofest (3), from the

Ronald Grant Archive (2, 5, 6). Pages 406-7: From the Ronald Grant Archive.

Pages 408-9: Courtesy of Robert Evans; copy work by Eileen Travell (1). From

Magnum Photos (2). From MPTV (5). From Photofest (3, 6). From the Ronald Grant

Archive (4). Page 411: From Photofest. Page 413: From Movie Still

Archives.